Thank you for this crucial question.

Aristotle believed that the highest human end is happiness, and that politics (or what Aristotle called “statesmanship”) is the science that directs the political community toward happiness. One possible consequence of this view is that what we nowadays call “science”—the systematic examination of the empirical world—is subordinate to politics in the sense that we pursue scientific ends ultimately for the sake of happiness. Two thousand years later, this still seems like a plausible idea: it is hard to believe that we would be justified in spending society’s resources on science if it did not contribute to general human flourishing.

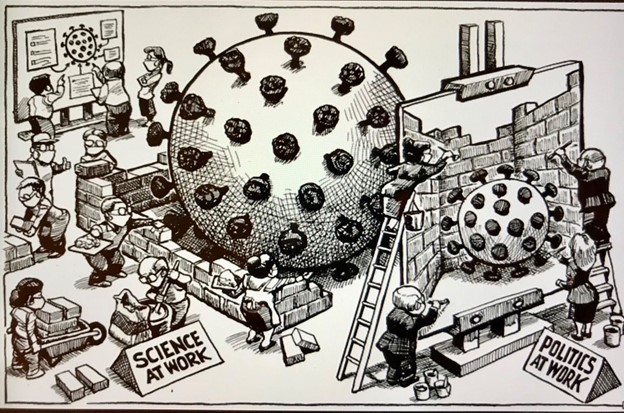

But this 30,000-foot view of the relationship between science and politics leaves many important details of that relationship unspecified. Perhaps it would be useful to look at the issue from the perspective of two stakeholders in the scientific enterprise: practitioners and members of society. Members of society have a rightful stake in the scientific enterprise because they contribute resources to it. We can also focus on two particularly relevant aspects of the scientific enterprise: funding and research agenda-setting.

It seems clear when it comes to research agenda-setting, members of society would want practitioners to pursue research agendas that are likely to contribute to their flourishing. But this does not mean that practitioners themselves should always have general flourishing in mind when setting their research agendas. First, it is not always clear which research agendas will promote flourishing, and it may be counterproductive to ask practitioners to try to guess. Second, practitioners may more assiduously pursue research agendas that interest them, which may ultimately produce better results for society than had they pursued research agendas consciously aimed at promoting general flourishing. (This point is similar to the hedonistic paradox, that pursuing pleasure for pleasure’s sake is self-defeating). For similar reasons, the fact that members of society have a legitimate stake in science does not mean that they should have direct control over agenda-setting.

How should scientific work be funded? The idea that members of society are stakeholders in the scientific enterprise might suggest that science should be funded by the public, and not by private interests. Again, however, I don’t think this follows. Science must benefit the public, but which funding arrangements will bring the most benefit is an empirical question, and not one that can be answered from—ahem—the armchair. That is to say: we cannot say that scientific activity will most benefit the public if it is entirely directed by some central government agency, entirely directed by market forces, or some mixture of the two. What we can say is that from the mere fact that science should benefit the public, it does not follow that scientific activity should be entirely directed by a central government agency.

What do you think? Should science be directed by politics? Let us know in the comments.

And, as always, if you have a question for the Armchair Philosophers, don’t hesitate to get in touch. You could send us a message or fill in this form.

Be sure to check out our podcast!

If you like what we do, you can support us by buying us a coffee!

Image: (credit)

I received my BA in philosophy from the University of Chicago and my PhD from the University of Notre Dame. I specialize in ethics, with a particular focus on the nature of normative reasons and the ethics of hypocrisy in its myriad forms. My favorite philosopher is Henry Sidgwick, since I believe—to borrow a line from Alfred North Whitehead, speaking about Plato—that much of analytic ethics in the 20th century is a series of footnotes to Sidgwick.

Savants governed by ignorants? Politicians dream of it…