Thank you, Eoin Martin, for this fascinating question.

I will assume that we are interested in whether good intentions matter for our moral evaluation of actions, and in particular whether good intentions morally justify an action. I will also assume that a ‘good’ intention is an intention that aims at something that is to some extent morally good – for instance, an intention to help a friend, to keep a promise, and so on.

Intuition seems to tell us that good intentions do not morally justify an action. For example, suppose a doctor intends to keep a promise to meet her partner for dinner. On the way to the restaurant, she drives past a car accident in which a number of people are severely injured and no one is attending to them. Despite seeing this, she continues on to dinner. Here, the doctor has done something morally wrong, despite intending to do something that is morally right – namely, keep her promise. So, good intentions are not enough to make an action morally justified. Now suppose the doctor intends to use drug A to kill a patient she doesn’t like, but mistakenly injects the patient with drug B, which happens to be the cure for the patient’s ailment. It seems as if giving the patient drug B is a morally justified action, even though the doctor did not do it with a good intention. After all, do we really want to say that the doctor ought not to have administered drug B?

Nevertheless, there may be more specific situations in which having a good intention is required in order for one’s action to be morally justified. Suppose that a certain action will have two effects: one good, one bad. Many philosophers believe that in order for one’s action to be morally justified, one must not intend the bad effect. For instance, if it is morally justified for me to stop a runaway trolley from killing five people by diverting it onto a track that has one innocent person tied to it, my intention must be to save the five, not to kill the one (and not to kill the one in order to save the five). So, in these kinds of cases – cases of so-called double effect – good intentions may matter.

There is another context in which good intentions certainly matter: when we turn from the moral justification of an agent’s actions to the praiseworthiness or blameworthiness of the agent herself on account of those actions. For example, in the case of the doctor who accidentally saved her patient’s life, we clearly would not think her praiseworthy for this action, precisely because she did not perform it with the right intention. Indeed, some might go so far as to say that only intentions matter when it comes to praise and blame. The argument, briefly, is this: we can be responsible only for what is under our immediate voluntary control (since everything else is at least partly determined by luck); only our intentions are under our immediate voluntary control; therefore, we are morally responsible only for our intentions.

In short, while intentions may matter less when it comes to morally justifying actions, they are extremely important, and arguably crucial, when it comes to the praiseworthiness or blameworthiness of agents.

What do you think? Do intentions matter? Let us know in the comments.

And, as always, if you have a question for the Armchair Philosophers, don’t hesitate to get in touch. You could send us a message or fill in this form.

Be sure to check out our podcast!

If you like what we do, you can support us by buying us a coffee!

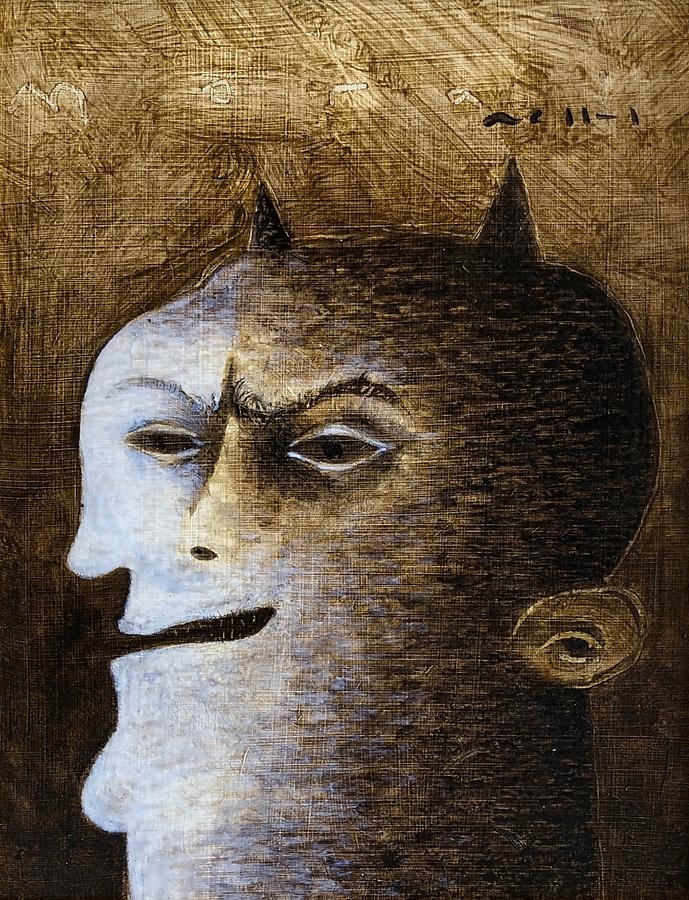

Image: Morals, by Mark M Mellon (credit)

I received my BA in philosophy from the University of Chicago and my PhD from the University of Notre Dame. I specialize in ethics, with a particular focus on the nature of normative reasons and the ethics of hypocrisy in its myriad forms. My favorite philosopher is Henry Sidgwick, since I believe—to borrow a line from Alfred North Whitehead, speaking about Plato—that much of analytic ethics in the 20th century is a series of footnotes to Sidgwick.