Thank you, Ali Muràád Bàloç, for this fascinating question.

The first thing we have to ask is, what is hypocrisy? Ask most people, and they will tell you that hypocrisy is not practicing what you preach. But consider this: in the process of becoming mature adults, we often do things that we later condemn, or condemn things we later do. On some occasions, this can amount to hypocrisy – particularly if we try to hide the fact that we previously engaged in the behavior of which we currently disapprove. Yet it does not have to be hypocritical to acknowledge that we have undergone moral improvement, and as a consequence currently disapprove of what we did in the past. So, not practicing what you preach is not enough to make someone a hypocrite.

I believe that what’s required, beyond the inconsistency between our words and deeds, is that this inconsistency manifests certain vices, which I call the “vices of hypocrisy.” These include self-righteousness, complacency, and pretentiousness – the last being the disposition to represent oneself as better than one is for the sake of some undeserved advantage. When we have undergone moral improvement, the fact that we preach against what we formerly practiced (or vice versa) is not necessarily a manifestation of any of these vices, and that is why it is not necessarily hypocrisy.

Given this definition, we are now in a position to ask whether people in fact live without hypocrisy. Unfortunately, this question is empirical: to answer it, we would have to assess whether there are people who never behave inconsistently in a way that manifests the vices of hypocrisy. This can’t be known from the armchair. The best that philosophy can do is to clarify what it is we’d be looking for if we were to embark on such a project, which is what I’ve tried to do so far. Based on our definition, it certainly seems possible to live without hypocrisy, although it might be quite difficult!

A more properly philosophical question is whether living without hypocrisy is desirable or right. We have seen that while it may be possible to live without inconsistency, if we want to morally improve ourselves it is probably not desirable to do so. But this kind of inconsistency need not amount to hypocrisy. This, together with the fact that hypocrisy always manifests vice, might be thought to clinch the case that it is never desirable to be hypocritical.

Yet there may be circumstances under which the best thing we can do is to be hypocritical. Consider a male employer who, secretly harboring sexist views but desiring to impress a female colleague, hires a well-qualified woman and treats her with outward respect. This is an act of hypocrisy, but I invite you to consider what you would advise the employer to do, if he came to you asking whether he should hire the well-qualified woman. He could act with “integrity” and hire the man he actually (though falsely) thinks is better qualified, or he could act hypocritically and hire the woman. There are a number of ways to analyze this case. First, we might see it as a case of one moral reason – a reason not to be hypocritical – being overridden by another moral reason – a reason to give the woman her due. Second, we might see it as a case of maximizing the good. In either case, we seem to come to the verdict that the right thing for the sexist employer to do is to be hypocritical. Thus, the answer to the question whether hypocrisy is desirable or right might be more nuanced than first appears.

What do you think? Is hypocrisy always wrong? Why? Let us know in the comments.

And, as always, if you have a question for the Armchair Philosophers, don’t hesitate to get in touch. You could send us a message or fill in this form.

If you like what we do, you can support us by buying us a coffee!

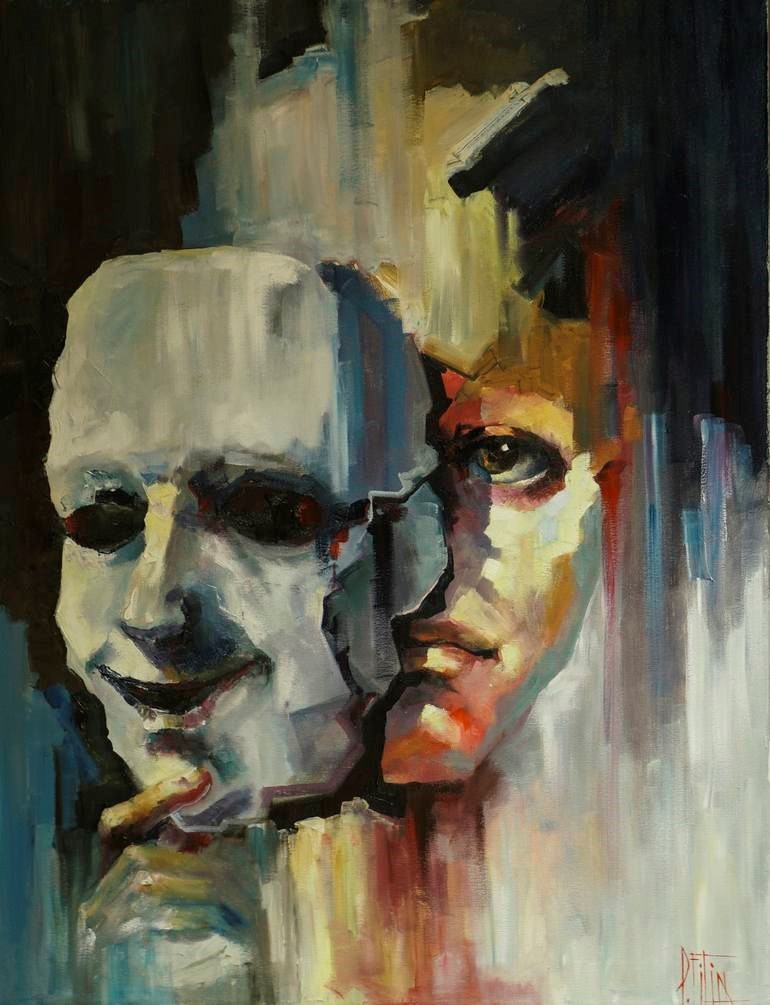

Image: hypocrite Painting by PAVEL FILIN (credit)

I received my BA in philosophy from the University of Chicago and my PhD from the University of Notre Dame. I specialize in ethics, with a particular focus on the nature of normative reasons and the ethics of hypocrisy in its myriad forms. My favorite philosopher is Henry Sidgwick, since I believe—to borrow a line from Alfred North Whitehead, speaking about Plato—that much of analytic ethics in the 20th century is a series of footnotes to Sidgwick.