Thank you, Ayli Inrovdop, for such a topical question.

A single vote hardly ever breaks a tie, so what’s the point in voting?

To begin, you could vote in the hope of having your own interests represented by the candidate or party that advocates for the policies most advantageous to you. After all, even though one vote does not make much of a difference, voting usually does not have high costs either. This is certainly a self-interested vision of voting, but not necessarily a condemnable one: your own benefit may be worth no more than anyone else’s, but it is worth no less either.

And yet self-interest is not the only reason why people make the effort to vote. There are also various motives of a more moral nature, which the “should” in your question is probably getting at. They usually refer to the consequences a vote can have.

To begin, you can vote with the purpose of making society more just, by choosing someone who makes wise decisions in this regard; if you think one of the candidates fits this description.

There are also other moral reasons to vote that are not primarily oriented at the outcome of a particular election or issue at stake, but rather at the more general consequences of the decision to vote at all.

First, one can argue that the habit of voting can make us better citizens and persons, like a sort of moral training. The more often we vote, the more we inform ourselves about what’s going on and think about what’s best for the community, the more we develop our abilities to reflect on the common good and make it a priority, and the better decisions we take. At least, this could be the case if we take this exercise with an open mind.

Second, one can invoke the notion of civic duty. In this perspective, voting means fulfilling a moral obligation to do our share for the community’s organisation, by participating in the effort to make the best decisions for the community. Seen this way, abstention comes down to a form of free-riding. Alternatively, one can appeal to the health of our democracies, by saying that democracy neither lasts long nor performs well if it is abandoned by its own citizens. Common to these two arguments is the idea that if everyone decided not to vote, we would lose a most valuable good (democracy). As you see, the civic duty to vote is a matter of principle, but this is because of the positive consequences voting has if it is a widespread habit.

There is one reason to vote that can apply in any case: gratitude. Gratitude may be understood as the virtue of being thankful for what we have and not taking it for granted. In a country with free elections, the right to vote may be seen as a privilege: in comparison to authoritarian regimes; or, depending upon a country’s political history, because it is a right people had to fight hard for. Such gratitude refers to the goodness of our character as a person who understands the moral meaning of political participation.

As we have seen, there are several moral reasons why we should vote, in principle. But that does not mean that we should always vote. Perhaps you think that your country’s current representative system does more harm than good; for instance, by tolerating unjustifiable inequalities and rights violations. This would raise a question: Does voting for a candidate or party more inclined to justice than others remain the right thing to do (a better-than-nothing approach)? Or would it not be more judicious to just stop supporting a morally broken system? If you go for the second option, you may believe in other, more appropriate means of promoting a just society, such as volunteering, organising political actions, or writing political pieces. In a deeply flawed political context, this may well be the approach you should adopt.

All in all, there are different moral reasons to vote and even not to, but what emerges from a review of them is that there is one reason not to vote that is not morally satisfactory: because one does not wish to ‘waste’ some of their free time thinking about what’s good for one’s political community.

What do you think? Will you vote in your next election? If so, or if not, let us know why in the comments.

And, as always, if you have a question for the Armchair Philosophers, don’t hesitate to get in touch. You could send us a message or fill in this form.

Be sure to check out our podcast!

If you like what we do, you can support us by buying us a coffee!

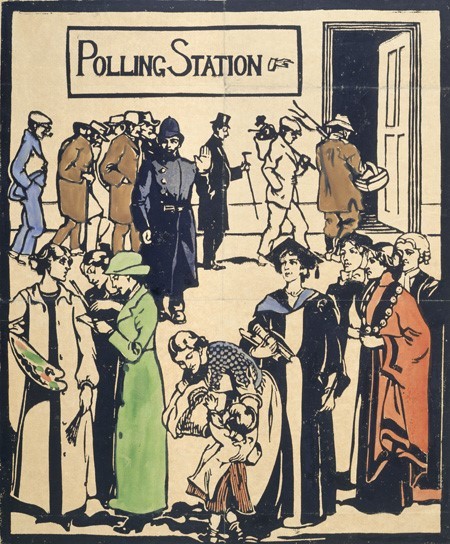

Image: The Polling Station, 1912; a suffragette postcard (credit)

I studied philosophy at the universities of Lausanne, Vienna and Bern, and I am currently finishing my PhD thesis on the concept of political consent (what does it mean to consent in politics?). My areas of specialization lie in early modern philosophy and contemporary political philosophy. I also have a keen interest in ethics, Ancient philosophy, and public philosophy. Thomas Hobbes would be my favourite philosopher, not because I agree with all of his conclusions, but because I love the clarity, precision and comprehensiveness of his writings.