Thank you, Kurt Elarcosa! A classic question, and timely too! If ever there was a year that prompted a question like this, it’s 2020. Let’s get to it.

First, we need to distinguish between evil and suffering, as they are actually mutually exclusive. Physical suffering, pain, can come from growth or healing, as in growing pains in childhood or being sore after a surgery. Pain from accidents are instances of pain that are not necessarily the result of evil. Emotional suffering can be similarly experienced as growth or healing; for example, the pain felt due to a failed exam or the end of a toxic relationship. Disappointment is a type of suffering that is a result of the world not living up to our standards, so you could say that it is of our own creation, not God’s. However, physical and emotional suffering caused by the ill will of others is something different. Intentionally causing physical and emotional pain is what lies at the heart of our conception of evil.

Evil, then, is the real object here. Why does evil exist? This has been debated fiercely since the introduction of the one “omni-you-name-it” God. One suggestion, based on Plato’s Timaeus, is that the world was not created by this God, but by a demiurge who only imitated the creative capacity of the greater God. Since this demiurge was not the greater God, his creation was lacking in goodness, and therefore contains evil. But we can skip past this idea, as we’re investigating the existence of evil in a world created by the one God.

If we shift our focus from the evil in the world to the goodness of God, we can begin to entertain other explanations. What does goodness mean when we refer to God? What qualifies as “good” varies from person to person, so how can we say that God is “good” with any objectivity? Scholastic philosophers, inspired by Thomas Aquinas, had the idea of tackling this problem by way of analogies: in particular, the “analogy of proportion” and the “analogy of attribution”. The analogy of attribution explains that the goodness we ascribe to a morally strong person and the goodness we ascribe to God are not the same; they are similar, but not the same. By this line of reasoning, our expectations of goodness can be very different to what goodness truly is in God. Likewise, what we say is evil may be very different than what God would say is evil.

The analogy of proportion has roots in neoplatonic thought, whereby creation (the world and its inhabitants) springs forth from its source in God through a series of emanations; and as you move through the emanations the creation becomes less and less like God. Imagine that a line of people were at a well and the first person tried to pass water to the last by cupping her hands, taking water from the well, and pouring it into the cupped hands of the person behind her. When the last person holds out their cupped hands to receive the water, there’s nothing left but a few drops. In this way evil doesn’t really exist as such, but only as a privation, degradation, or lack of good. This way of looking at it is incredibly helpful if you have an idea of redemption.

This discussion can go on for days, but in the end a shift of perspective can do a lot for us when we try to make sense of the uglier parts of existence.

What do you think? If God is all-powerful and all-good, then why is there evil in the world? Let us know in the comments.

And, as always, if you have a question for the Armchair Philosophers, don’t hesitate to get in touch. You could send us a message or fill in this form.

Be sure to check out our podcast!

If you like what we do, you can support us by buying us a coffee!

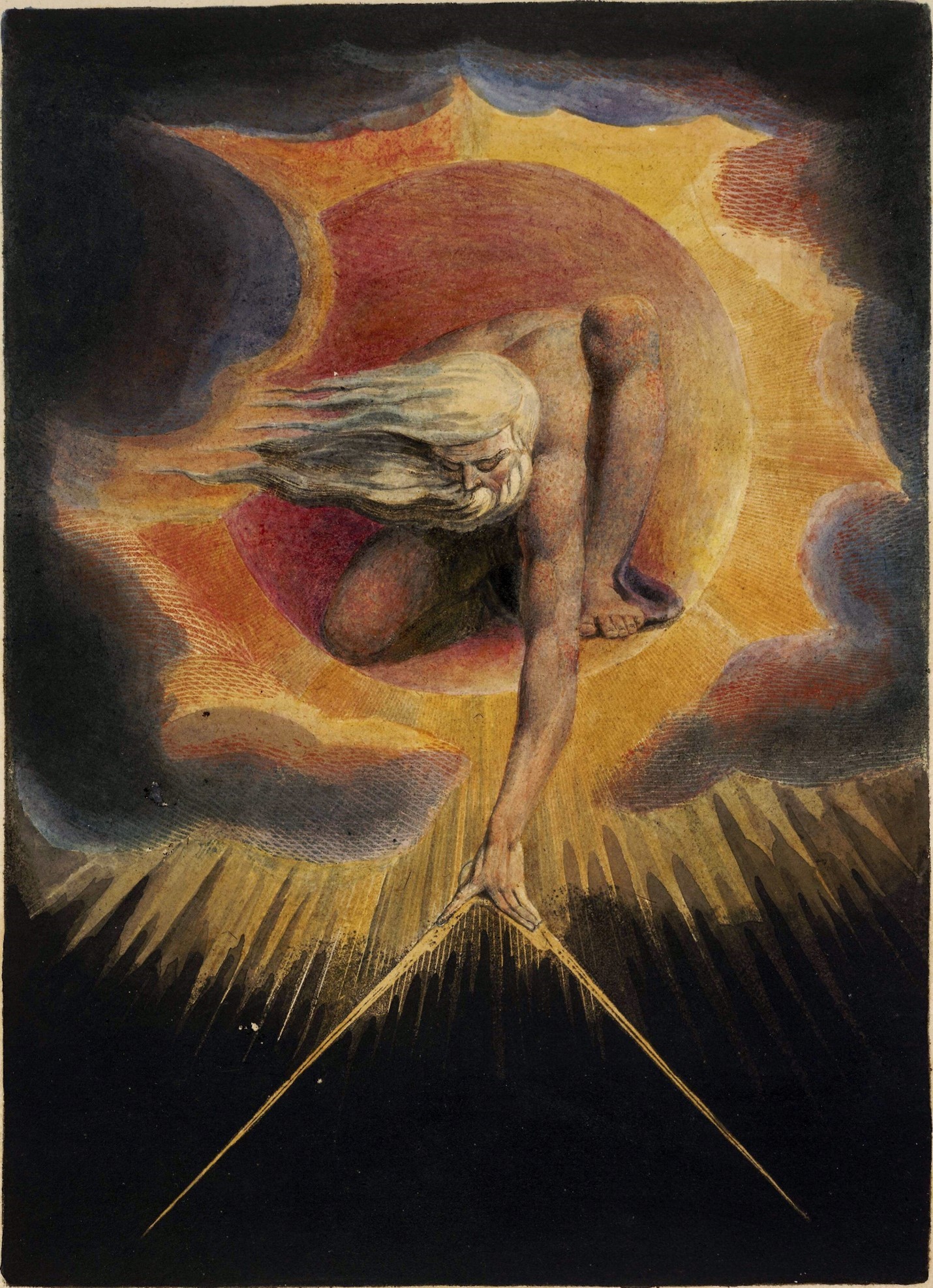

Image: William Blake’s Ancient of Days (1794)

I received a BA in philosophy from the University of Texas at El Paso in 2008. After that, I spent roughly a decade traveling Europe and North America as a touring musician. Now I am working on a master’s in philosophy and philology at the University of Gothenburg in Sweden with the goal of teaching at the university level. Some specific areas of interest include medieval grammar and free will. Michel Foucault’s approach to the history of philosophy has been a huge influence on me, and his work on notions of the self and power structures bring history to the present.