Thank you, Tanay Baswa, for this wonderful question! I hope you won’t mind if I start by discussing something slightly different: Why did we start smiling in photos?

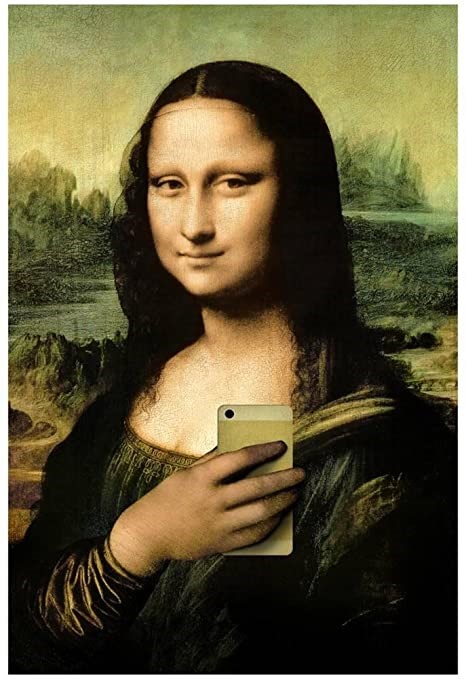

If you look at Victorian photographs, you will instantly notice a difference to our modern-day selfies: nobody is smiling! Try going further back in time and look at painted portraits hanging in museums: nobody is smiling either. Even though people say that Mona Lisa became famous for her mysterious smile, the truth might be even simpler: she is memorable because she actually has a smile.

There are many reasons why people did not smile as much as we do. For instance, dentistry was not as well developed as it is today, so a great number of people had crooked, decayed or even missing teeth – no wonder they did not want to show them off. But another, even more important reason is that smiling was just not a serious thing to do.

Look at your passport photos. Are you smiling? Of course not. This is an official document; you are not supposed to smile. Originally, photographs were also somewhat official: they were taken by professionals for great sums of money and most often either accompanied an important life event – a wedding, a funeral, maybe a child’s first communion – or were something to be passed on to future generations, like the only remaining photograph of your great grandmother. They served the specific purpose of documenting these big events and helping maintain the memory of the people photographed.

Things are different now, of course; it all changed with the introduction of cheap, consumer-oriented, portable cameras. Suddenly, people were able to take more than a just few photographs over the course of a lifetime, snapping dozens of them in a single weekend trip. Photographs left the family lockbox and became something to be shown to others. The goal was no longer to have just a picture, but an ideal picture.

Of course, this does not mean that the Victorians did not want to look ideal, just that for them a photograph served a different purpose: it was probably supposed to project respectability, not happiness or intimacy. But as times changed, so did our idea of what should be seen in photographs. Today we not only smile in photos, but we also do countless other things to make ourselves look the way we want others to see us, things our ancestors would probably frown upon. It might mean sucking in your belly or putting our arms around each other, even though we might never show this level of affection without cameras present. While photographs might be perceived as representing reality, they are always a piece of fiction that is ultimately created by performances we prepare specifically for the lens of the camera. We might not be aware that we are trying to meet some social expectations or conventions, but cameras do not capture the way things are; there is always the decision about what to keep in the frame, what to leave out, how to arrange the objects in view, when to press the button…

In the end, you could just try asking yourself, what would you look like in your wildest fantasies? Would you be rich, famous, surrounded by friends? Maybe. But you would definitely be smiling. And this is the ideal you instinctively try to project in your photos; it is how you want to be seen.

What do you think? Why do we smile in photos? Let us know in the comments.

And, as always, if you have a question for the Armchair Philosophers, don’t hesitate to get in touch. You could send us a message or fill in this form.

Image: Chengyidianzi Mona Lisa Selfie

I did a BA and MA in Philosophy at the University of Warsaw, where I focused on philosophy of technology, hermeneutics and social philosophy with a Marxist slant (which I was suprisingly able to combine in my MA thesis on Gianni Vattimo). I am currently working on a PhD at Dublin City University, where I research self-tracking technologies and practices from the perspective of virtue ethics. My favourite philosophical idea is that our understanding and beliefs change across history and cultures together with material circumstances and the interpretative context – they are ultimately the result of our choices and critiques.