Thank you, Ian Castañares, for such a great question. I am pretty sure I know how to answer it.

I believe I speak for most philosophers when I say that sceptics are simply the worst. No matter how well-reasoned and well-structured your argument, there is always somebody who just stands there with their arms crossed and speaks those dreadful words: “Sorry, not convinced.”

Don’t get me wrong, doubting is fine, especially when it arises from some genuine flaw in a statement. But the worst sceptics are those that just don’t care. They will question everything, just for the sake of it, because they are not fully convinced that any knowledge is possible. Common sense assumptions? Not sure about that. Logical conclusions? But logic also has its flaws. First-hand experience? Our senses can deceive us. For a true sceptic, doubt is always reasonable, because you cannot be wrong if you believe in nothing; and so you should doubt everything.

But this approach has its problems. Hardcore scepticism would require us to also doubt doubting itself, that is, to question the validity of the process that allows us to do any questioning in the first place. But doubting doubt implies that we should not doubt anything, which would in turn prohibit us from doubting doubt. Although classical sceptics are famous for inventing paradoxes that invalidate our common sense understanding, true scepticism also ends in a contradiction.

Moreover, in order to doubt something, you need to understand its meaning and you often need to express your doubt in a linguistic way. You cannot say that you do not believe that a sentence is true if you do not have a concrete belief about the meaning of the sentence. Any true sceptic should refrain not only from questioning their doubt, but also from questioning the rules of language as a whole. True scepticism is impossible, because doubt needs its limits in order to serve a purpose.

Too much scepticism leads toward something absurd and counterproductive. There is some worth in doubting – that is why Ian asked to what extent doubt is reasonable and not whether it is reasonable at all. Doubting serves an important role in the production of knowledge, because it allows us to examine our own beliefs, identify their weak points, and either improve upon or discard them. But doubt taken to the extreme would just be impractical: if you spent all day wondering whether anything can be trusted, you would get nowhere and, perhaps more importantly, you would deny yourself the chance of being wrong, which is sometimes a roundabout way of getting to the right answer. Doubt enough to be able to revise your own convictions and to never accept something uncritically: check if the source is credible, question the authority on which the claim is made, try to see if the logic is solid. These are sceptical tools that will make your convictions more justified. But if you doubt too much, it becomes an exercise in itself: a counterproductive diversion, not a process aimed at improving the foundations of our often flawed knowledge – and that would be unreasonable. How to achieve the perfect balance between insufficient and excessive doubt is another question, and even I would be sceptical whether a definite answer can be found here.

What do you think? Is there a point at which doubt becomes unreasonable? Let us know in the comments.

And, as always, if you have a question for the Armchair Philosophers, don’t hesitate to get in touch. You could send us a message or fill in this form.

Be sure to check out our podcast!

If you like what we do, you can support us by buying us a coffee!

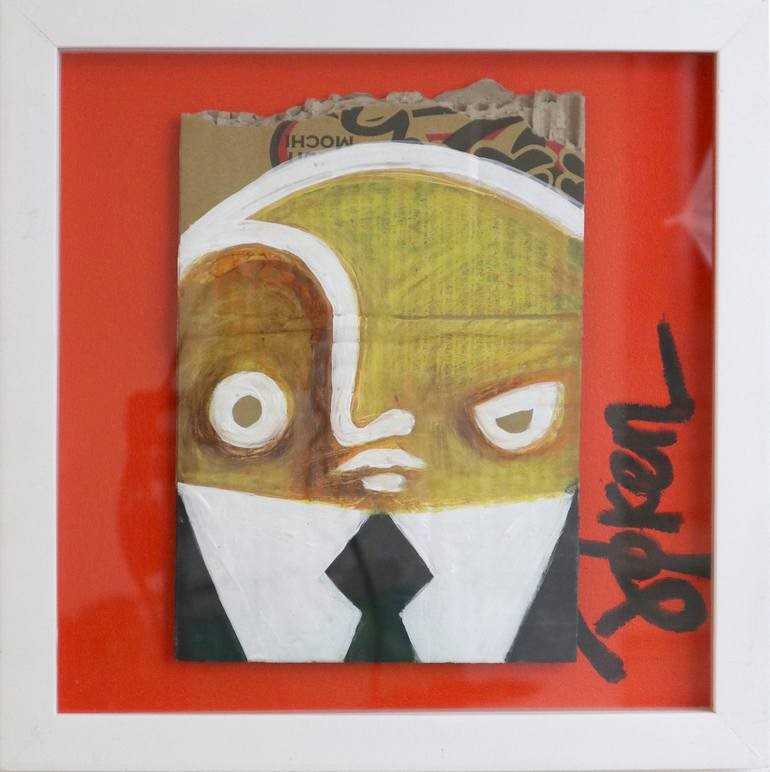

Image: The Sceptic Painting, by Jøken art (credit)

I did a BA and MA in Philosophy at the University of Warsaw, where I focused on philosophy of technology, hermeneutics and social philosophy with a Marxist slant (which I was suprisingly able to combine in my MA thesis on Gianni Vattimo). I am currently working on a PhD at Dublin City University, where I research self-tracking technologies and practices from the perspective of virtue ethics. My favourite philosophical idea is that our understanding and beliefs change across history and cultures together with material circumstances and the interpretative context – they are ultimately the result of our choices and critiques.