Thank you, Frankie Belton, for such a stirring question!

When we ask a question about whether something (A) is necessarily something else (B), we are asking whether there can ever be an A that is not also a B. In other words, what we are asking is not whether there are A’s that are also B’s, but whether A is going to always, INEVITABLY, also be B.

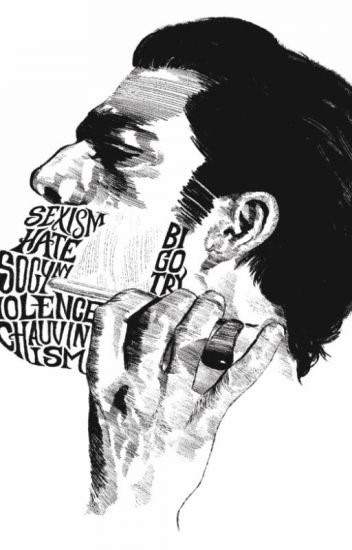

So, in the case of masculinity (A) and toxicity (B), what we are asking is whether there is masculinity that is not toxic, or whether masculinity, in any form, will INEVITABLY be toxic. Importantly, asking this question is not to deny that there are many Tapout-clothes-wearing, tribal-tattoo-having, ammosexuals who embody a deeply toxic masculinity, but just whether some form of masculinity can be saved from these protein-shake-guzzling hordes.

In response to problematic (i.e. obviously toxic) forms of masculinity, some have suggested that the culture has simply obscured the ‘true’ idea of masculinity. To be masculine is to embody a certain ahistorical type, usually involving traits like bravery, intelligence, fortitude, and pretending to like whiskey. It is important to note that there are concepts that do have an ahistorical status (like the concept of a triangle). If masculinity was this sort of concept, then there would be necessary characteristics that would make up what masculinity is. In order to find the non-toxic masculinity, one need only separate the unnecessary characteristics from the necessary ones. If we do this, a ‘pure’ masculinity would emerge separated from its toxic forms.

At least two criticisms to this approach can be voiced: (1) The concept of masculinity is not the same sort of concept as a triangle. Unlike a triangle, masculinity is a culturally defined role that is dynamically responsive to social change. When we begin to try to define ‘true’ masculinity, we find that masculinity has had dramatically different expressions in different times and places, and so resists an essentialist definition. (2) Any attempt to treat masculinity AS IF it were an ahistorical concept (when it is in fact not) is necessarily toxic insofar as it enforces a culturally relative norm as if it were of the ahistorical type. Furthermore, given the historical and cultural use of the concept of masculinity (the domination/exploitation of women and non-conforming males), attempts to distill a ‘pure’ masculinity from historical sources will inevitably reproduce these prejudices. So, it might be said that all attempts at ahistorical definitions of masculinity are necessarily toxic.

Notice that if masculinity is a culturally dynamic social role, then it is not necessarily anything, including toxic. In other words, if masculinity is just a collection of cultural expressions, then there is not anything that necessarily ‘belongs’ to masculinity, including toxicity. Furthermore, this does not mean that there is NO SUCH THING as masculinity. Defining masculinity as a socially dynamic role does not mean it dissolves into nothing. Rather, social roles, and their culturally responsive definitions, provide us with an important language of expression. In order to function as a language of expression, some level of stability is required. For instance, we can think of LGBQT+ folx who, while denying the essentialist picture of gender identity, still use traditional expressions of masculinity and femininity (such as drag kings/queens) as ways to express their own gender identities. In the same way, describing Dwayne ‘The Rock’ Johnson as masculine is an accurate use of a cultural expression. The use of masculine expressions (short hair, big muscles, smoldering eyes, etc.) is still an invocation of the concept of masculinity, though perhaps in a non-toxic way.

What do you think? Is masculinity necessarily toxic? Let us know in the comments.

And, as always, if you have a question for the Armchair Philosophers, don’t hesitate to get in touch. You could send us a message or fill in this form.

Image: (credit)

I have a Masters degree in Philosophy from the University of South Carolina where I wrote a thesis on Immanuel Kant’s political philosophy under Konstantin Pollok. I am currently doing a PhD at the University of Groningen (the Netherlands) in the project “Universal Moral Laws” under Pauline Kleingeld. I am interested in Kant’s legal and political philosophy as well as contemporary jurisprudence and republicanism. Predictably, then, my favorite philosophical work is Kant’s Groundwork to the Metaphysics of Morals. This work contains, in my mind, some of most important ideas for the possibility of universal and objective moral laws.