Thank you, Andy Chartier, for such an intriguing question.

Very generally, science is a methodological investigation into physical phenomena that aims at describing the actual world with the highest possible precision. Morality is an inquiry into what sorts of things we ought to value (compassion over hate) and what sorts of things we ought to do (help and don’t harm others).

So, strictly speaking, the idea that science could determine morality would mean that I could start with a descriptive ‘is’ statement (‘humans are omnivorous’) and end up with a prescriptive ‘ought’ statement (‘humans ought to eat meat’). This is what is commonly known as the naturalistic fallacy or the is/ought fallacy. The idea is that one cannot move directly from a descriptive claim to a prescriptive claim, because nothing in a descriptive claim (that something is the way that it is) implies a prescriptive claim (something ought to be some other way). An ‘ought’ statement gives us an imperative based on values, while scientific descriptive statements are based on facts.

But even in science we must presuppose values that shape the way we treat empirical evidence, and these values cannot be explained by empirical evidence themselves. For instance, the scientific value of (good) evidence shapes the pursuit of science (by defining good science and science backed up by good evidence). Yet, that we ought to pursue good evidence is an imperative that cannot itself be proven by scientific investigation. Any attempt to do this would invoke the standard which we are trying to prove. So, even scientific values cannot be determined by science.

Yet, suppose that we do presuppose some fundamental value for morality, perhaps well-being or human flourishing. Can science determine how we can bring about the most human flourishing/well-being? Yes, of course, in the following sense. What we mean by ‘human flourishing’ can be explained by scientific investigations into the ways that humans function. If I want to understand what is best for my cat (his name is Gilbert), I should read the latest research on cat care. This would, in theory, generate obligations, like I ought to brush Gilbert’s fur twice a month. However, it seems that science has trouble even with this task, and for two reasons.

First, the reasons that this sort of scientific model can generate are only prudential reasons. In other words, science might determine the best way for me to achieve the objective value of health, but science can only give me reasons relative to some desirable goal. What it cannot give me are moral reasons, that is, reasons that are directed toward the wrongness/rightness of an action (e.g. I ought not murder because it is wrong). In this sense, science cannot give us an explanation of why murder is wrong, but only why murder might not promote human flourishing.

Second, in order for science to determine what promotes the most well-being, there needs to be some standard by which it is measured. But what would such a measurement look like? Unless we are willing to accept that well-being is reducible to measurable brain-states, it seems as though science will have a hard time distinguishing between relative states of well-being or human flourishing.

What do you think? Can science determine morality? Let us know in the comments.

And, as always, if you have a question for the Armchair Philosophers, don’t hesitate to get in touch. You could send us a message or fill in this form.

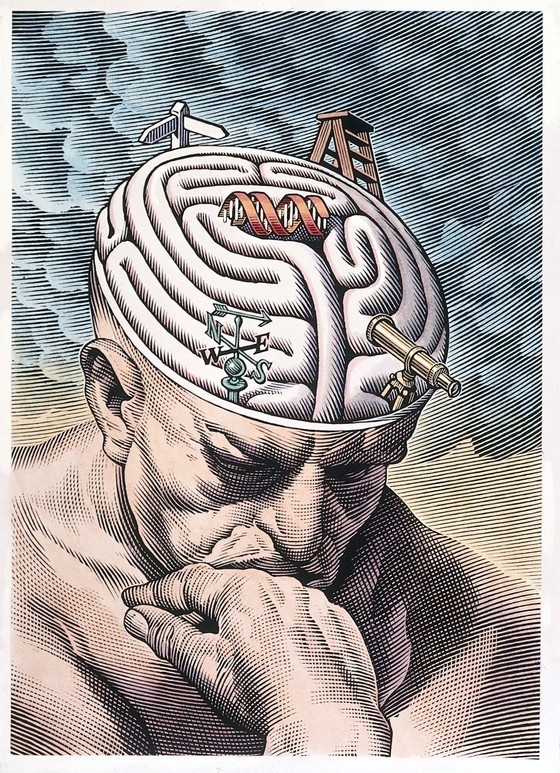

Image: (credit)

I have a Masters degree in Philosophy from the University of South Carolina where I wrote a thesis on Immanuel Kant’s political philosophy under Konstantin Pollok. I am currently doing a PhD at the University of Groningen (the Netherlands) in the project “Universal Moral Laws” under Pauline Kleingeld. I am interested in Kant’s legal and political philosophy as well as contemporary jurisprudence and republicanism. Predictably, then, my favorite philosophical work is Kant’s Groundwork to the Metaphysics of Morals. This work contains, in my mind, some of most important ideas for the possibility of universal and objective moral laws.