How practical is it to not fall into the trap of good vs evil dichotomy?

Thank you, Kirti Lamba, for this fascinating question.

It is difficult to define the concepts ‘good’ and ‘bad’, if by “define” we mean analyzing these concepts into better-understood constituents. For example, it’s not clear that we can do to ‘good’ what we do to ‘bachelor’ when we define that concept as ‘unmarried male’. Other philosophers have attempted to define ‘good’ and ‘bad’ in terms of reasons: for example, they say that what it is for X to be good is for X to have features that give us reasons to want X.

Still, all agree that we can distinguish different senses of “good”. Sometimes “good” is used in an attributive sense to mean “good of a kind”. For example, a good hammer is a hammer that functions well as the kind of thing it is, as is a good car and a good husband. (But what about a good person?) Another sense of “good” is the sense we use when we say that Y is good for X, as when we say that medicine is good for you. Here we mean that Y benefits X, although we probably can’t define ‘benefit’ in a way that does not invoke the concept ‘good’. Some, but by no means all philosophers think that there is also a predicative sense of “good”, as when we say that pleasure or beauty are good. This is a controversial idea, since if some things are good in this sense, they may be neither good for anyone nor good of a kind – this is why some people call this sense “good in an unqualified sense”. The same distinctions apply to “bad”: we can say that some things are bad of a kind, bad for someone, and perhaps unqualifiedly bad.

There also appear to be many senses of “evil”. Sometimes we use the term to describe things that are just really bad, either of a kind or for someone (e.g. “cancer is an evil”). Nietzsche thought that ‘evil’ combines the idea of bad with the idea of moral agency: roughly, X is evil when X is a bad action and someone is morally responsible for X. Sometimes, evil describes the psychological profile of agents: for example, some agent X is evil if she takes pleasure in other people’s suffering.

There is a hidden assertion behind the second question, which I think is roughly as follows: understanding agents or actions as either “good” or “evil” is a “trap” because (a) it discourages us from understanding them in greater depth and/or (b) it does not capture any moral ambiguity – when something is neither good nor evil. The first point is psychological; the labels “good” and “evil” can inhibit understanding because of their emotive charge. The second point is more philosophically interesting. First of all, it seems clear that not all actions or agents need be good or evil, since “good” and “evil” are logical contraries, not contradictories. That is to say, while nothing can be good and e

vil, something can be neither good nor evil. For example, pouring milk into a bowl of cereal is an action that is neither good nor evil. But this kind of action is not generally what we mean when we say that something is morally “ambiguous”. When we say this, we may mean merely that we don’t know whether something is good or evil. More interestingly, we may mean that it has both good and evil parts. Sometimes it is difficult to weigh these parts to arrive at a final judgment about their worth. This, it seems to me, is true moral ambiguity. We can resist falling into the trap – if it is a trap – of labelling something either good or evil if we attend carefully to the fact that actions and agents are complex, usually “containing” both good and evil parts.

What do you think? What’s the difference between good and evil? Let us know in the comments.

And, as always, if you have a question for the Armchair Philosophers, don’t hesitate to get in touch. You could send us a message or fill in this form.

Be sure to check out our podcast!

If you like what we do, you can support us by buying us a coffee!

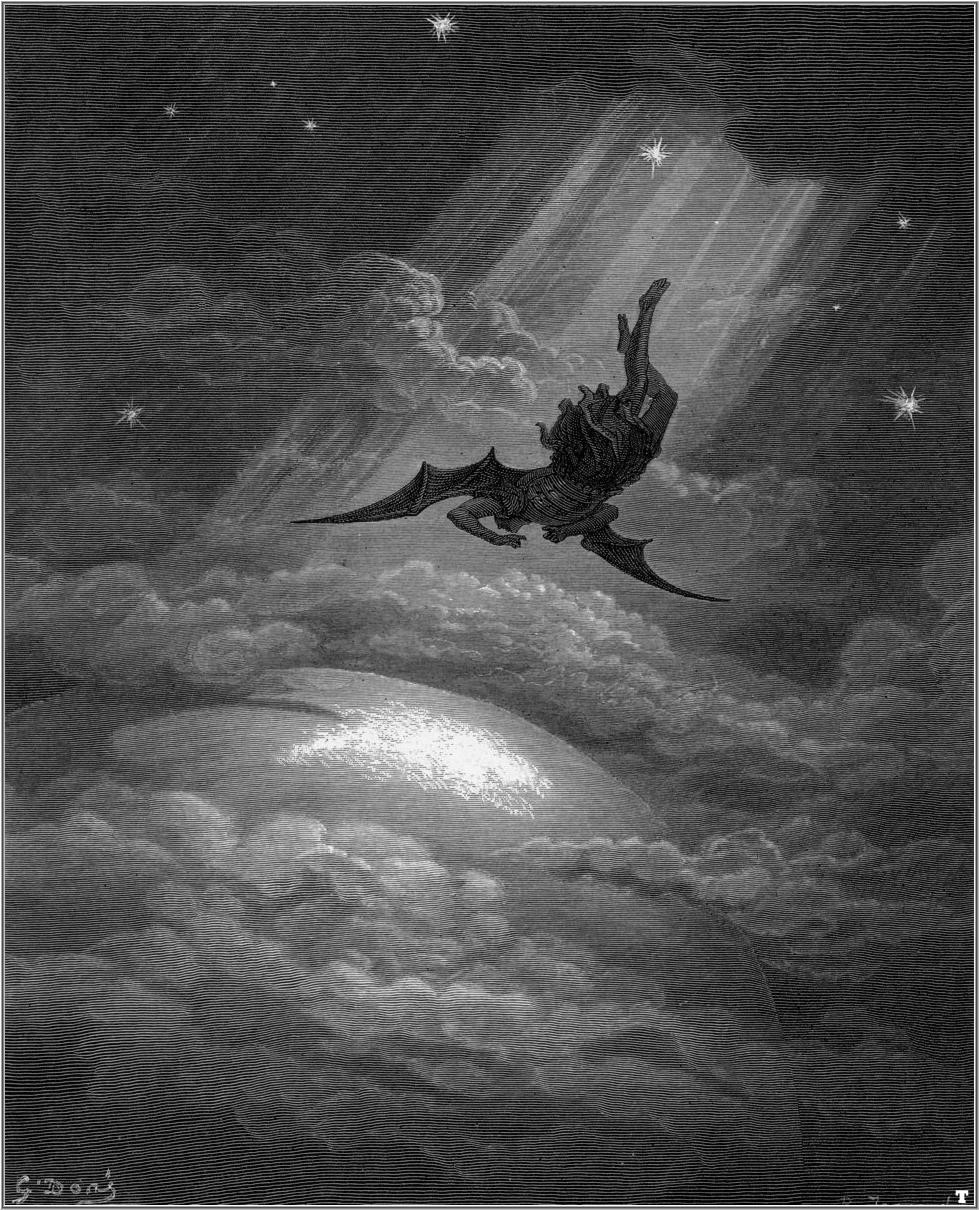

Image: Gustave Doré’s illustration for Milton’s Paradise Lost, III, 739–742: Satan on his way to bring about the fall of man

I received my BA in philosophy from the University of Chicago and my PhD from the University of Notre Dame. I specialize in ethics, with a particular focus on the nature of normative reasons and the ethics of hypocrisy in its myriad forms. My favorite philosopher is Henry Sidgwick, since I believe—to borrow a line from Alfred North Whitehead, speaking about Plato—that much of analytic ethics in the 20th century is a series of footnotes to Sidgwick.