Thank you, Eoin O’Sullivan, for an important question.

A common understanding of justice – namely, “distributive justice” – is that we distribute certain goods fairly across a certain population. Goods represent the fundamental interests of citizens. Some political philosophers have argued that there are certain “primary goods” that are universal across any given political community (rights, liberties, opportunities, income, and wealth), and that must be distributed fairly.

Walzer, however, denies that there are any primary goods that can capture the interests of all citizens of all political communities. Instead, Walzer insists that what counts as a good, and therefore what counts as justice, is defined according to the particular political community. This means that in order for there to be justice, we must first identify the sorts of things that the citizens are interested in, what they understand to be a “good”. Only then can we fairly distribute these goods.

This is Walzer’s “pluralism”. Not only are there many conceptions of justice, but also many conceptions of what counts as a “good” worthy of being considered for fair distribution. Walzer insists that what is “good” can be understood only from within a particular political community; their interests are particular to their shared understanding, shared meaning, and shared practices. Thus, instead of a theory of justice that is applied to a political community, Walzer provocatively suggests that the conception of a just order is already latent in our shared understanding of social and political goods.

However, Walzer’s view faces some objections.

First, Walzer is committed to the notion that existing political communities have a shared value system. This is supposed to be shown by the fact that political disagreements bottom out in a sort of appeal to a collective commitment to values, a group understanding of what is good and what the community is most interested in. However, this suffers from two simplifications. 1) In an era defined by political polarization, it seems obvious that there can be very different interpretations of the values that a political community is committed to. In other words, political disagreements are not only about how to manifest some shared values, but also about competing visions of what those values ought to be. 2) If political disagreements do share a commitment to a set of shared values, doesn’t this simplify the sorts of perspectives we find politically relevant? In other words, in a militaristic society, with a shared value of military strength, are minority interests in peace just irrelevant, or incoherent?

Second, Walzer (and many similar thinkers) have a hard time explaining how one can be critical of any given political community. Since Walzer thinks that whatever a political community puts into practice (universal health care, say) is just a manifestation of the shared understandings of that community, the only way to know what the community values is to look at what they do. However, if we always “derive” some value from some existing practice, then we end up in an endless feedback loop, always deriving our values from what the community actually does. In this case it appears impossible, or at least meaningless, on Walzers perspective to step back from practices, and even actual consensus, to reflect on what our values ought to be, and what we ought to treat as a good. Walzer makes values completely dependent on actual practice, rendering social/political critique meaningless.

What do you think? Where do our values come from? Let us know in the comments.

And, as always, if you have a question for the Armchair Philosophers, don’t hesitate to get in touch. You could send us a message or fill in this form.

Be sure to check out our podcast!

If you like what we do, you can support us by buying us a coffee!

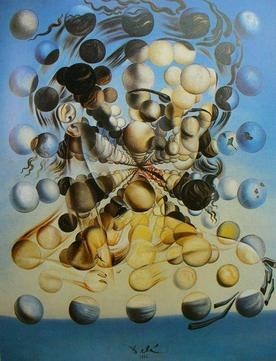

Image: Galatea of the Spheres, by Salvador Dali (1952)

I have a Masters degree in Philosophy from the University of South Carolina where I wrote a thesis on Immanuel Kant’s political philosophy under Konstantin Pollok. I am currently doing a PhD at the University of Groningen (the Netherlands) in the project “Universal Moral Laws” under Pauline Kleingeld. I am interested in Kant’s legal and political philosophy as well as contemporary jurisprudence and republicanism. Predictably, then, my favorite philosophical work is Kant’s Groundwork to the Metaphysics of Morals. This work contains, in my mind, some of most important ideas for the possibility of universal and objective moral laws.