Thank you, Arya Amritansu, for such an important question.

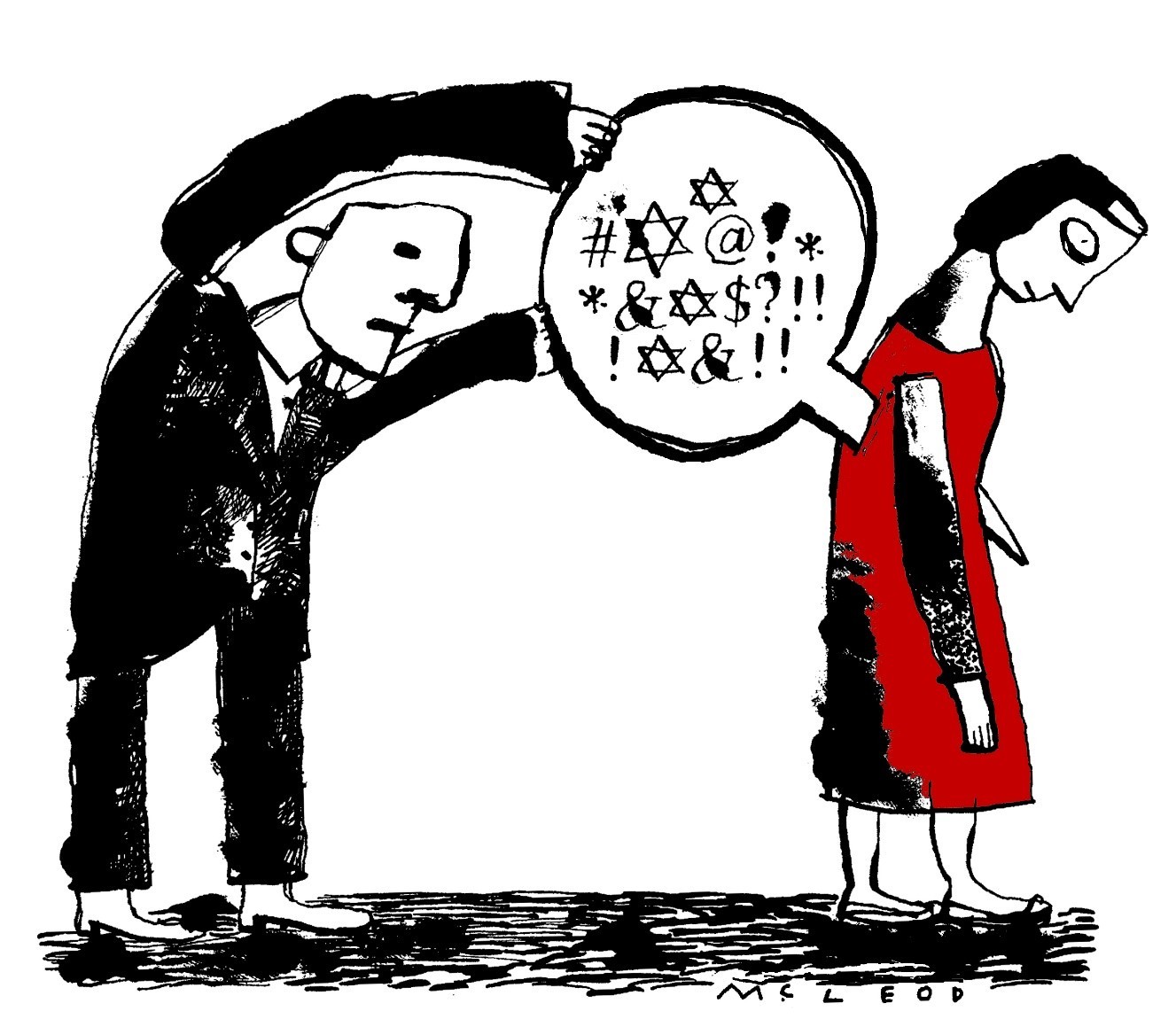

To answer these questions it is first necessary to clarify what we mean when we talk of “hate speech”. Hate speech is speech that attacks people in virtue of their membership in a racial, religious, ethnic, sexual or other group. In other words, hate speech is a form of identity-based contempt, which often calls to mind a history of violence and oppression against a particular group of people. There are two things to notice here. The first is that hatred is not sufficient to make someone’s speech hate speech. I may say something hateful to someone because, well, I hate them; but this does not qualify as hate speech if it has nothing to do with their membership in a particular group. The second thing to notice is that there is a difference between hate speech and offence. If someone tells me that my haircut sucks, I may be extremely offended, but that doesn’t qualify their remark (unkind as it is) as hate speech.

Having clarified what hate speech is, let’s now try to understand why it causes harm. Philosophers have given different answers to this question – as always! Some, like Jeremy Waldron, have argued that hate speech is an attack on dignity, which undermines individuals’ ability to participate in the political life of a society on an equal footing with others, thereby creating and maintaining hierarchies. This is what philosophers call a consequentialist view: hate speech is harmful because of its effects, on both individuals and society as a whole.

Another common consequentialist answer to the question of why hate speech causes harm is that it encourages violence against members of particular groups. A group that is constantly vilified and verbally attacked is more likely to be physically attacked as well – as recurrent events involving brutality against black people in the United States have shown.

Now, the fact that hate speech causes harm may not be the only reason why hate speech is harmful. It could be argued that hate speech is harmful in and of itself, regardless of its consequences. Hate speech is harmful because of what it expresses. Philosophers of language since J. L. Austin have argued that we do things with words: in saying something, we do something with what we say. In the case of hate speech, we could say that in treating people as inferior we thereby subordinate them. The harm is in our very act of speech.

But how is that measured? This brings us to the second part of the question. And the short answer is: it is very difficult to do so, especially if we consider not only the harm caused by hate speech, but also the harm represented by such speech itself. In fact, philosophers very much disagree on the extent to which hate speech harms, even though they mostly agree that some harm occurs. Hate speech may work in subtle yet pervasive ways. The problem with not being able to quantify the harm in hate speech is that it becomes difficult to justify regulations to restrict or ban such speech. If hate speech is harmful, should it be regulated? Is there sufficient ground to regulate it, even if the harm itself cannot be quantified? I guess these are my questions for you.

What do you think? What is so harmful about hate speech? Let us know in the comments.

And, as always, if you have a question for the Armchair Philosophers, don’t hesitate to get in touch. You could send us a message or fill in this form.

Image: Cinders McLeod Illustration (credit)

I did a BA in Philosophy at the University of Bologna, followed by an MA, MPhilStud and PhD at Birkbeck, University of London. I currently work at Birkbeck and King’s College as a teaching assistant, delivering seminars to CertHE, BA and MA students. My areas of expertise are political philosophy, ethics and gender. I am also interested in business ethics, ethics of science and technology, applied ethics and politics, and the history of political thought. My research focusses on liberal multiculturalism, autonomy and vulnerability. I am fascinated by the idea of freedom, its history, and its recent developments in political theory.