Thank you, Heather Bennett, for such a timely question…

I happened to be watching Tiger King recently (along with everyone else, no doubt). It was episode 3. Carole Baskin was talking about an argument she had had with her first husband. She said, ‘I deal with stress the same way cats do: I just pace and pace and pace and pace.’ But cats do not deal with stress by pacing; it is not natural behaviour. What Carole meant to say, I am sure, is that she deals with stress the same way captive cats do. Captive cats certainly deal with stress by pacing; or perhaps it is more accurate to say that the peculiar stress of being in captivity often manifests as pacing. The same can be seen in other captive animals, including humans: prisoners in solitary confinement often pace, but so do other humans – why?

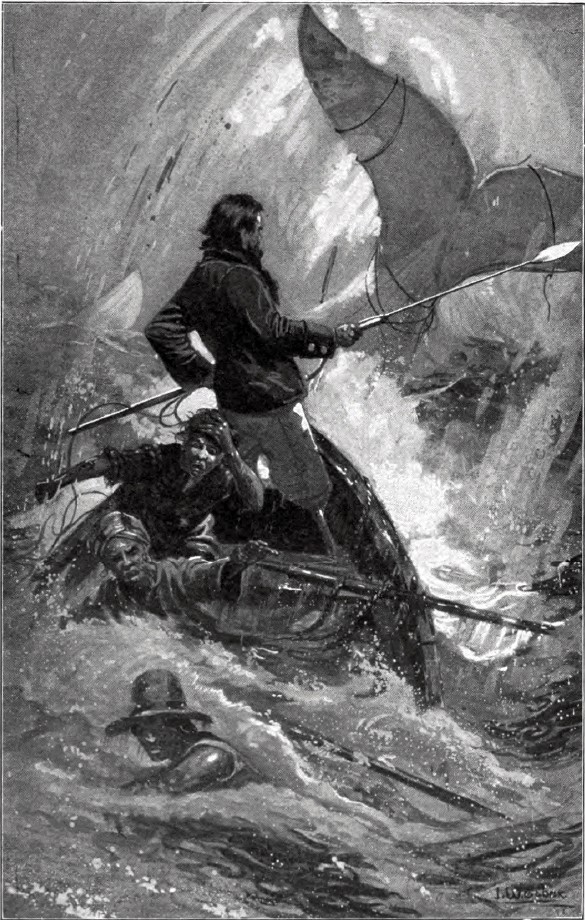

As well as watching Tiger King, I also happen to be reading Moby-Dick (I am having a whale of a time in lockdown, honestly). It was Chapter 36. Ahab was pacing: ‘… so full of his thought was Ahab, that at every uniform turn that he made, now at the main-mast and now at the binnacle, you could almost see that thought turn in him as he turned, and pace in him as he paced; so completely possessing him, indeed, that it all but seemed the inward mould of every outer movement.’ What was the thought that so possessed Ahab? It was none other than that of the White Whale, Moby-Dick.

But Ahab was no captive, far from it: he was the captain of a ship (namely, the Pequod) and free to sail the seven seas – about as free as anyone could ever hope to be. Why, then, was he pacing? Alas, Ahab was still a captive: not in space, granted, for he was free to sail in any direction he pleased; no, Ahab was a captive in time, that is to say, his fate was sealed. Who was his captor? It was his unrelenting desire to exact revenge against Moby-Dick for having bitten off his leg. So, whereas before we had a person holding an animal captive in space, here we have an animal – or, at least, the thought of one – holding a person captive in time. Perhaps it was the dichotomy between his complete freedom in space and his complete confinement in time that made Ahab’s condition so torturous.

Hang on a second. Ahab wasn’t real; he is a fictional character. How can he help us understand why real life people pace? Well, Ahab’s condition is just a rather dramatic example of an everyday phenomenon – that’s how good fiction works, right? There would be little sense writing about something to which no one could relate. So, from Ahab’s condition, fictional though it may be, we may nonetheless derive an explanation as to why real life people pace, perhaps as follows.

Ahab was simply stuck heading in a certain direction, one which, for him, ended in disaster. In real life, it is rarely so dramatic. It all starts with a desire for something; it could be anything, but usually something career- or family-oriented. When we are young, such desires pull us in a certain direction. But, when we are older, when the greater part of our lives is behind us, the direction of force changes: where there was once a desire pulling us forward from up ahead, there is now a hope pushing us forward from behind; it is the hope that the journey thus far wasn’t all for nothing, that it may still amount to something worthwhile. The point in time when the direction of force changes is usually around the time people have mid-life crises; and it is the combined force of the desire and the hope that holds people captive in dead end jobs and dead end relationships. And so they, like Carole’s tigers and Moby-Dick’s Ahab, have little else left to do, but pace.

What do you think? Why do people pace? Let us know in the comments.

And, as always, if you have a question for the Armchair Philosophers, don’t hesitate to get in touch. You could send us a message or fill in this form.

Image: Ahab in his final chase with Moby-Dick

I did a BA in Mathematics and Philosophy at Lancaster University, followed by an MPhil in Philosophy at the University of Warwick. I spent a lot of time studying Kant (his first Critique), the philosophy of mind, and the philosophy of language. My favourite philosophical idea is Quine's idea that the common-sense theory about physical objects and the gods of Homer are both just posits; the only difference is that the theory of physical objects turned out to be more efficient – that was the last idea to truly blow my mind.