Thank you, Jayle Paña, for such a sensitive question.

Hope is a belief in the possibility of some goal or, more generally, toward the destiny of human beings or the world. A state of hopelessness is one in which there are many signs and much believable evidence that point in the opposite direction of our “hoped-for” outcome. Many of us know what it feels like to be in a state of hopelessness. There seems to be no, or very little reason to hold on to hope that things will still advance toward some desirable goal.

Let’s take an example: world peace. In this pessimistic age, saying you have hope that we can achieve world peace seems naive, if not downright irrational. Any casual glance at the news will surely crush any remaining optimism you have and convert you into a pessimist who grumbles about the pointlessness of it all in the corner of a pub at 2pm on a Tuesday.

And yet, there are those who, despite seemingly obvious evidence to the contrary, still insist that “the arch of the moral universe bends toward justice”. Martin Luther King Jr., who is perhaps the modern personification of hope, said this well-known phrase in the midst of a fight for Civil Rights, one which would eventually take his life. Why, and how, did he continue to hope?

In the same speech, King makes claims that we all live in two realms: “that realm of spiritual ends expressed in art, literature, morals, and religion for which at best we live” and “that realm of instrumentalities, techniques, mechanism by which we live”. King suggests that the great tragedy of life is “that we too often allow the means by which we live to outdistance the ends for which we live”. It seems that King’s point here is that when we allow the standards of practicality to become the standards by which we judge the ends we hope for, it is indeed hard to maintain hope.

However, the first realm cannot and should not be judged its practicality, or it will be quickly given up when we find some watered-down alternative to be more expedient. In other words, spiritual ends (moral progress, world peace, perfect justice, religious salvation) are adopted and justified by different standards than the merely pragmatic ends we adopt every day. The possibility of pragmatic ends can and should be judged by real world evidence (like the possibility of making an infinite source of energy). Yet, adopting world peace as an end is not desirable because it is or isn’t pragmatic, but because it is good in itself. If this is the case, then the admittedly large amount of real-world evidence that counts against the pragmatism of adopting world peace as a hoped-for end does not actually count against it. We hope for world peace because it is good, not because it is pragmatic. Some ends are not adopted based on their feasibility.

Notice, also, that no amount of real-world practicality would render world peace a logical impossibility. It is possible to achieve world peace, even if it isn’t feasible. I think that this is enough to call hope for world peace, even in hopeless situations, rational. We continue to hope because peace is desirable in itself, and we will continue to desire it, even when it doesn’t seem feasible.

What do you think? Why do people hope? Let us know in the comments.

And, as always, if you have a question for the Armchair Philosophers, don’t hesitate to get in touch. You could send us a message or fill in this form.

If you like what we do, you can support us by buying us a coffee!

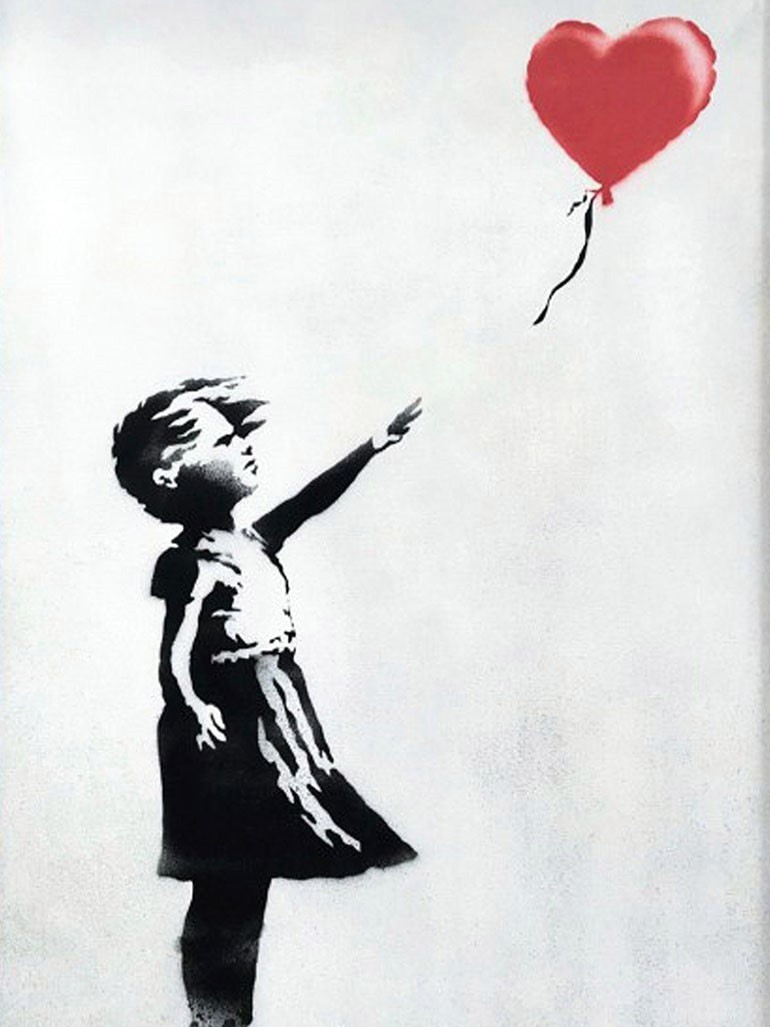

Image: Girl with Balloon, a mural by Banksy (2002)

I have a Masters degree in Philosophy from the University of South Carolina where I wrote a thesis on Immanuel Kant’s political philosophy under Konstantin Pollok. I am currently doing a PhD at the University of Groningen (the Netherlands) in the project “Universal Moral Laws” under Pauline Kleingeld. I am interested in Kant’s legal and political philosophy as well as contemporary jurisprudence and republicanism. Predictably, then, my favorite philosophical work is Kant’s Groundwork to the Metaphysics of Morals. This work contains, in my mind, some of most important ideas for the possibility of universal and objective moral laws.