Thank you, Alex Impey, for such a weighty question.

Being in love and loving – that is, romantic love and non-romantic kinds of love – seem to overlap in astonishing ways: both share features such as attachment, attraction, warmth, and interest. That said, being in love certainly feels different to loving – why is that? One reason may be the presence of a kind of sexual desire, which we usually associate with the feeling of arousal. Arousal is a raw feeling, not unlike the feeling of orgasm. Raw feelings aren’t about anything; they have no object. In this respect, they contrast with lust, which is about the object of desire, and is akin to romantic love. Neither orgasm nor arousal seem to be necessary for romantic love. I can have both feelings without an object – that is, an object of romantic love or sexual desire. Is lust or sexual desire necessary? Maybe. But perhaps romantic love is not the only kind of love which involves sexual desire or lust. Could there be, for example, friendly love with sexual desire or lust? Possibly.

It seems, then, that feelings of arousal or lust or sexual desire aren’t enough to account for any difference between being romantic and non-romantic kinds of love. Maybe we should take into account what scientific research shows. It seems to be the case that romantic love has a different chemical profile to non-romantic kinds of love: romantic love is more like a syndrome. So, if this is correct, romantic love is not in fact an emotion; and, unlike emotions, it is ‘arational’, that is to say, it is insensitive to reasons. Non-romantic kinds of love, on the other hand, are sensitive to reasons; for example, reasons to love your friends.

But why is romantic love arational? Perhaps it is because we tend to idealise the object of romantic love. But the same seems to be applicable to non-romantic kinds of love. Don’t most of us (except for my mother and some others) idealise our parents, children and friends? So perhaps non-romantic kinds of love are arational, too. Yet, our intuitions still tell us that we have reasons to love. At least, Lady Gaga cites some for her bad romance.

What do you think? What’s the difference between love and being in love? Let us know in the comments.

And, as always, if you have a question for the Armchair Philosophers, don’t hesitate to get in touch. You could send us a message or fill in this form.

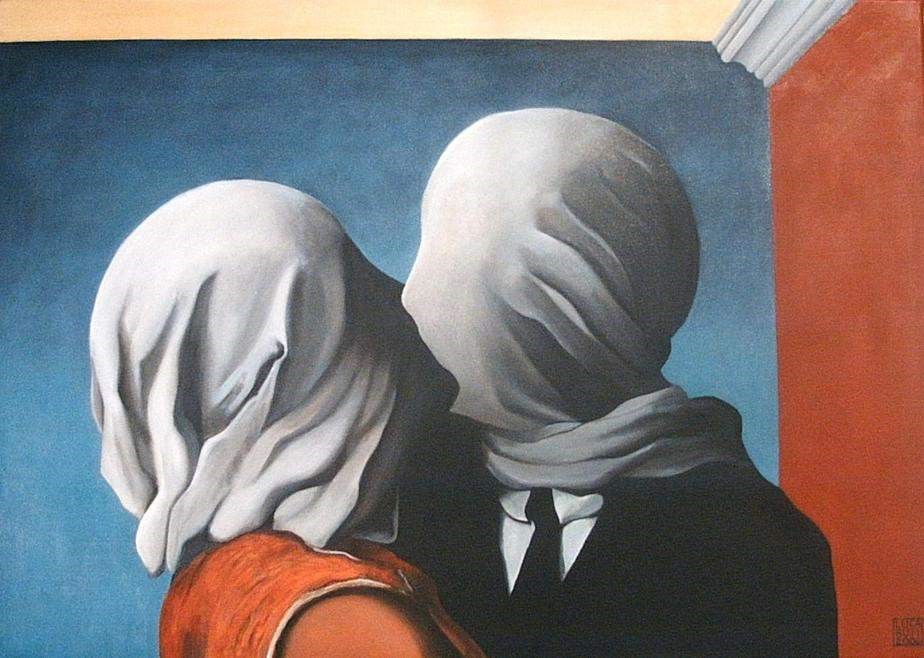

Image: The Lovers, by Rene Magritte (credit)

I did an MEng in Civil Engineering at Cardiff University and an MA in Philosophy at the University of Warwick. I spent some time studying Nietzsche and the history of philosophy, but since then I have focused mostly on the philosophy of mind and philosophy of emotions. One of the most recent ideas I have found interesting (and crazy for our standards) is the revision of panpsychism (coming in varieties like protopanpsychism). This is the view that mental properties may ultimately be fundamental like physical properties. If this is right, then it may be that in the future, psychophysical laws are going to explain the conscious experiences associated with the physical processes explained by physical laws.