“Apparently, there is a 50-50 chance that we live in a simulated world. What does philosophy make of this possibility?”

Thank you, Wynn P Wheldon. Actually, this question has been central to philosophy for a very long time now, and, as usual, there is no simple answer to it. It raises attached questions, such as: Can we prove that we do not live in a simulation? How can we step out of our own experience of reality? How can we say with certainty that what appears to us is real and objective, and not merely some personal, subjective perception?

These kinds of questions predate any technology that could provide us with a virtual reality; it is even fair to say that when these doubts first arose, people could not even imagine such technology. We can find one of the first approaches to life as a simulation in the 17th century philosophy of Rene Descartes.

Descartes realised that our senses can very often deceive us and, what is more, that we make sense of our senses using our minds. He then started to look for certainty in his own cognitive processes and discovered that he always had reason to doubt what he was thinking. Take your question, for example: we can easily find reason to doubt whether the reality in front of us actually exists. Descartes came to the conclusion that all he could be certain of was that everything can be doubted. The first version of his famous ‘cogito ergo sum’ – ‘I think therefore I am’ – was actually ‘dubito ergo sum’ – ‘I doubt therefore I am.’

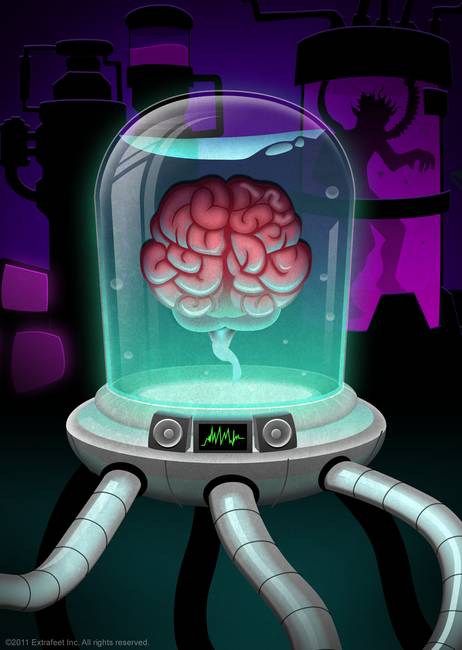

Descartes was looking for something that he could be certain of, and found that we are unable to conceive of reality outside of the doubts, outside of our own thoughts. This statement largely defines how modern philosophy is practiced. Since Descartes, one of the main tasks for philosophy has been to try to establish how we can actually prove that there is some form of objective reality if we can only ever relate to it with our own thoughts, with no way to escape our minds. If everything is happening in our minds subjectively, how can we prove that the world out there is not a simulation? As in a famous thought experiment, how can we prove that we are not just brains in vats that are trapped in a simulated reality?

The most common counterarguments come from scientific methods of proving that something is ‘true’ and real. If many people repeat an experiment in the same conditions on many occasions and the results are the same each time, thanks to inter-subjectivity we can take the result as an objective truth, that is, as something that is true outside of our own minds… But what if all the brains were exposed to the exact same form of simulation?

Others would rely on faith. If we conceive of god as a good creator who is not trying to deceive us, we can be certain that reality exists… But what if the concept of a god is part of a simulation?

Some people are simply realists, who take the hard facts of the world as proof enough that what is real is real. In the end, the majority of us are convinced that the reality in front of us is real and it would be “crazy” to think otherwise… Or is it just a really convincing simulation?

Despite hundreds of philosophers trying hard for hundreds of years to find a definitive answer to this question, there is still no consensus. If you ask, there is quite frankly a 50-50 chance, because either it is a simulation or it is not.

What do you think? Does the possibility that it is all just a simulation affect the way you live your life? Let us know in the comments.

If you have a question for the Armchair Philosophers, don’t hesitate to get in touch. You can find us on Twitter (@armchair_o) or fill in this form.

Be sure to check out our podcast!

If you like what we do, you can support us by buying us a coffee!

Image: (credit)

I am a PhD candidate in Political and Social Thought at the University of Kent, Canterbury. I am researching modern Western cosmologies and approaches to organicism. My interests lie in the area of continental political thought, process ontologies and the philosophy of technology. My favourite philosophers are A.N. Whitehead and F.W.J. Schelling, whom I admire for their organic systematizations of nature and natural knowledge.