Thanks, Kenth Hubert Badiang Francisco! This question is as old as philosophy itself, with the ancient Greeks being especially interested in it.

For some, a good life is one in which we have some positive subjective state—like when we experience the fulfillment of some desire or other. For others, it is one in which we live a morally good life, which gets defined in various ways.

Suppose you think a good life is just a life full of satisfied desires. This is a subjective understanding of the good life and it certainly seems like a life I would want to live. Such a life would be one in which I accomplished all my goals (say, becoming a tenured professor). One problem with this idea is that it suggests that a highly successful serial killer could live a good life in the same way Mother Teresa did. For example, the Zodiac Killer assaulted and killed many people and was never caught. Assuming the Zodiac desired to be a successful serial killer, he would have experienced a high amount of desire satisfaction and therefore lived a good life. This is a bad result.

Some form of the bad-person-who-lived-a-good-life objection afflicts all the basic subjective theories we can think of. So, if we still feel that subjective views of the good life make sense, we will need to say something about why such objections miss the target, or else we need to say why they are not actually problematic.

What about saying that the virtuous life constitutes the good life? This is a version of the idea that a good life is one in which we are morally good. There is something attractive here since living a courageous, kind, generous, and just life sounds like a life we should all want to live. This, after all, is a life in which we would presumably do good for others and ourselves by being virtuous. One issue is that it seems consistent with virtue that I also be homeless my whole life. In that case, I might live my life in accordance with virtue, but nevertheless be so unlucky that nothing ever goes my way. Should we say that the virtuous but unlucky and homeless person lived a good life? I am not sure we should—they might have lived a moral life, but their life was not good.

Importantly, any version of the morality-based option is going to have to say why this objection is not a problem or does not apply. So, it seems both kinds of simple suggestion have problems.

Notice that these are really simple suggestions. Natural next questions are: Would any combination of these work? Can we adjust one of these so that it can deal with the proposed problem? These are questions I leave as food for thought.

What do you think? Desire fulfilment or morality? Let us know in the comments.

If you have a question for the Armchair Philosophers, don’t hesitate to get in touch. You can find us on Twitter (@armchair_o) or fill in this form.

Be sure to check out our podcast!

If you like what we do, you can support us by buying us a coffee!

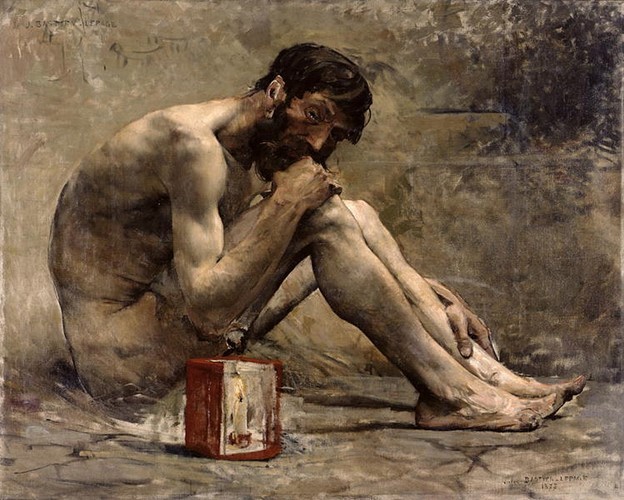

Image: Diogenes (1873) by Jules Bastien-Lepage. Diogenes was a Greek philosopher who made a virtue of poverty.

I have been doing philosophy since 2012 and am currently working on my PhD at the University of Kent. I have a BA from Oklahoma Baptist University and an MA from the University of Florida. I am currently most interested in ethics-related issues of various kinds. My favorite works of philosophy, at present, are Aristotle's Nicomachean Ethics and, for very different reasons, David Enoch's Taking Morality Seriously.