Thank you, Austin Birch, for a great question. When I say “great”, I mean not only “fantastic”, but also “great in magnitude”, because exegesis is a huge concept within the history of philosophy. After all, as Whitehead put it, Western philosophy is nothing but a series of footnotes to Plato’s dialogues.

To start, I’d like to offer a quick response, which is: No, I don’t think that true exegesis can ever be achieved. Everything we use to interpret reality is so loaded with cultural and personal baggage that we are unlikely to be able to make sense of anything in a purely objective way. But I also don’t think that true, objective readings of texts are what we should be aiming for. This cultural and personal baggage I mentioned comes into play not only when reading, but also when writing a text. To engage with this idea, I looked to Michel Foucault’s article, “What is an Author?”

When we read a text, we create a relationship between ourselves, the text, and its author. If we are to make a thorough attempt at an unbiased reading of the text, then we must first define who we are as the reader, where the boundaries of our biases lie, who the author is and what their goal is in writing the text. Once they are defined, they must be shed (let me know if you figure out how to do this). This goes for the biases on both ends. But I am afraid that without these biases, all we are left with are empty symbols and signs (unless the text contains some sort of objective truth that can be universally interpreted).

Foucault’s article reveals that there have been several functions for the authorship of a text. At times in antiquity, we see less emphasis on specific authorship in exchange for the context of the text itself. Homer is a good example: Homer made no attempt to identify him/her/themself; there is no biographical information intended to give us a picture of the author. This could be because what was important was the account of the interactions between gods and men given in the text. This contrasts with later antiquity and the Middle Ages, when the validity of a text was deeply tied to the authority of its author, as we see in numerous commentaries. At other times, the role of the author is emphasized in an attempt to achieve some sort of immortality or status. So, we can see that interpreting a text can begin before ever reading a word.

If we are to fully understand a text, we must understand not only its words, but also its function, its placement in time, and the biases of the author. With this as the goal, recognition of our own biases is paramount, because it is the only way for us to truly understand where the reader ends and the author begins. This could be seen as reading a text objectively. But I think that if you switch your own rose-tinted glasses for another’s rose-tinted glasses, the color of the world remains distorted.

What do you think? Can a text ever be read objectively? Let us know in the comments.

And, as always, if you have a question for the Armchair Philosophers, don’t hesitate to get in touch. You could send us a message or fill in this form.

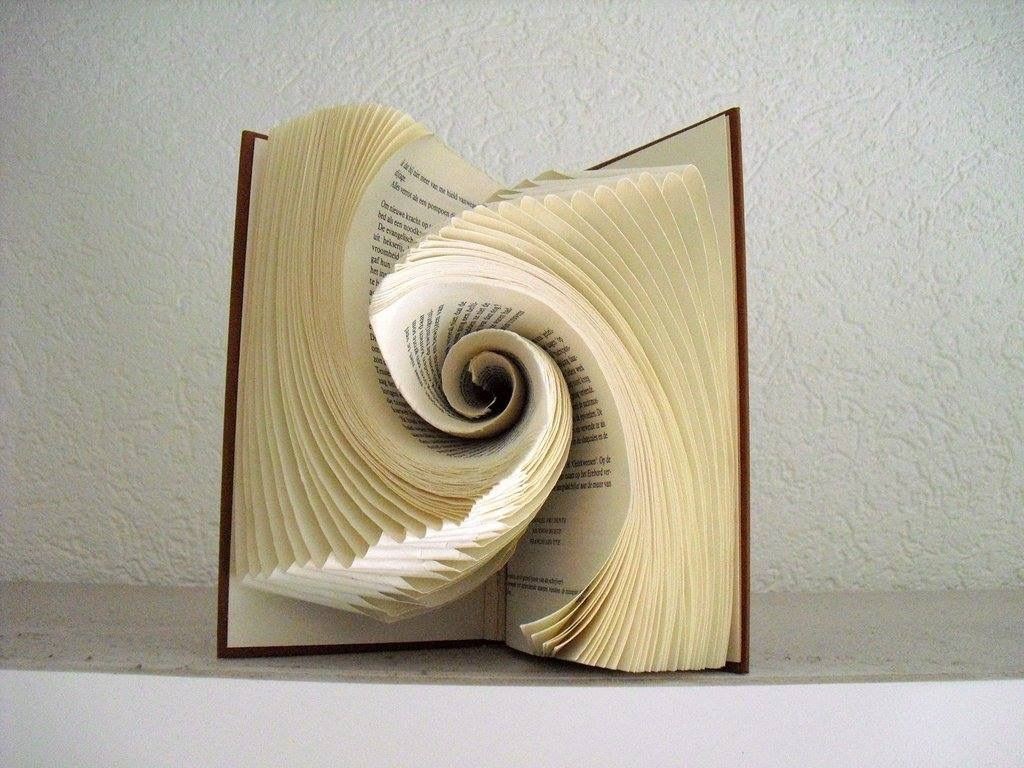

Image: (credit)

I received a BA in philosophy from the University of Texas at El Paso in 2008. After that, I spent roughly a decade traveling Europe and North America as a touring musician. Now I am working on a master’s in philosophy and philology at the University of Gothenburg in Sweden with the goal of teaching at the university level. Some specific areas of interest include medieval grammar and free will. Michel Foucault’s approach to the history of philosophy has been a huge influence on me, and his work on notions of the self and power structures bring history to the present.

No matter how deep we go in uncovering our own presupposition, we can never remove them, only identify that they are there. Nor can we remove the presuppositions of the author whose words we read! So TRUE exegesis is not possible.