Thank you, Joshua Genovea, for such a pertinent question.

Your question is discussed by Machiavelli in his famous book, ‘The Prince’. Machiavelli advises rulers to inspire both fear and love in their subjects; but if they cannot obtain both, fear would be the safer bet. This is not only for the ruler’s own interest in keeping rivals and rebels away to stay in power. There is, arguably, another reason that lies in the nature of authority: a prince needs his subjects to be compliant with his orders to be able to govern. Otherwise, if subjects just do as they please, what’s the point of having a ruler?

Machiavelli assumes here that fear is the most effective motivation for us to do something that we don’t naturally desire to do, like obeying authorities. As an illustration, let us take taxes: a lot of people pay them, not because they’re happy to, but because they fear the punishment of the state if they refuse to, which would mean losing even more money, maybe even going to jail.

Machiavelli also thinks that if subjects love their prince without being afraid of him, they will be more easily inclined to “offend” him; by disrespecting his orders, for instance, or abusing his clemency. Note that Machiavelli hastens to add that such fear should not turn into hatred. Tyranny is usually not tolerated long by subjects, who had better resist it than endure it, unlike the rule of a strict, but fair prince.

If Machiavelli is correct, fear is not only good for the prince, but also for everyone benefiting from the goods he provides. Nowadays, such goods would include, for instance, the protection of our rights, infrastructure such as roads or water systems, education, public health systems, or social aid for those who need it (at least this is what we tend to expect from governments). Thus, if fear is a necessary ingredient to keep a political community in line, it does not seem that unreasonable to consider it a valuable political asset, if not the most enchanting one.

But I am not sure Machiavelli is right about the risks of love. In politics, does love really exclude listening? One could also say, against his position, that a loved prince is a prince who does not need the threat of force to have his orders obeyed. A prince may be loved by his subjects because he is perceived to be wise, responsible, just, or caring for his people (why else would we love him?). Orders and statements issued by such a prince may sound naturally convincing. But perhaps Machiavelli sees citizens as too ungrateful, or rulers as too corrupt, for this to be a likely scenario.

What do you think? Feared or loved – which is better for a leader? Let us know in the comments.

And, as always, if you have a question for the Armchair Philosophers, don’t hesitate to get in touch. You could send us a message or fill in this form.

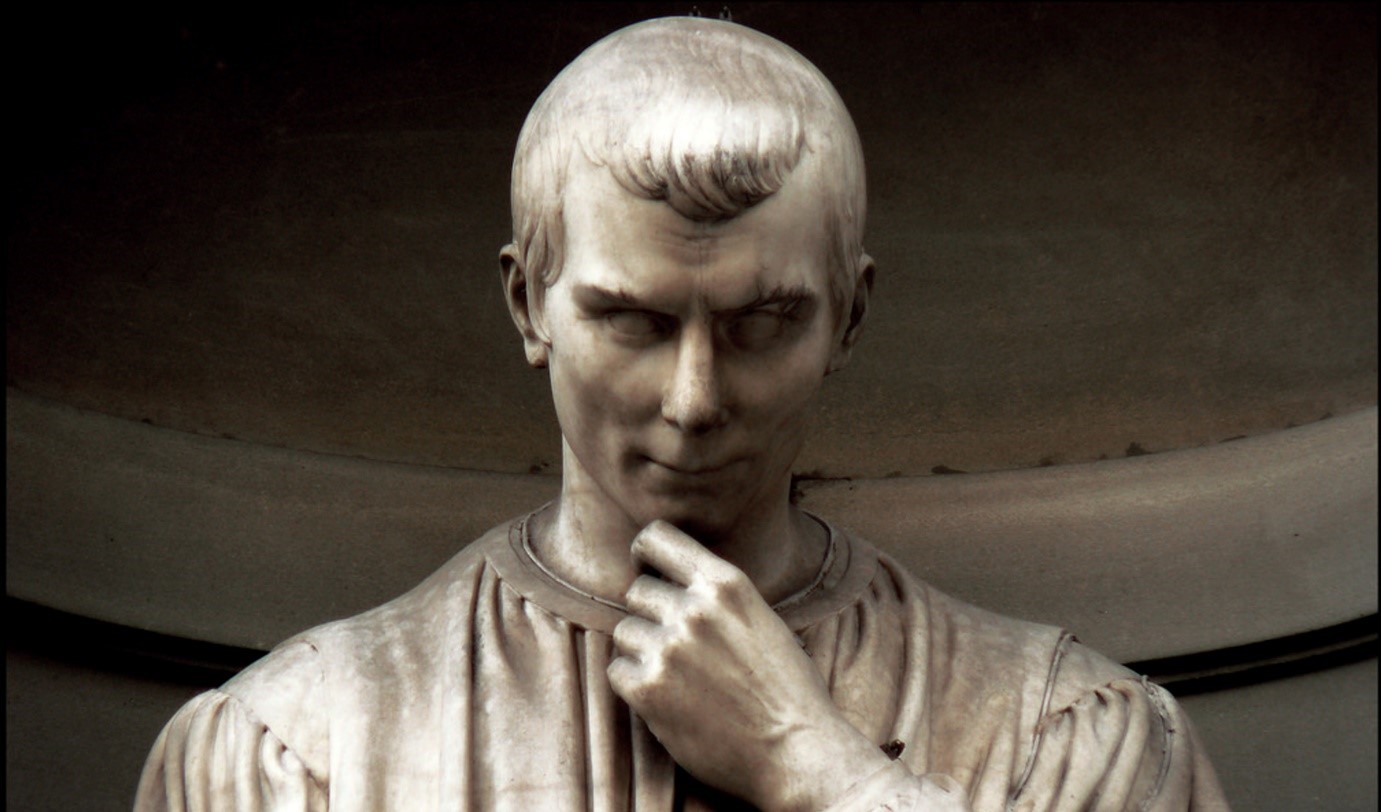

Image: Niccolò Machiavelli, by Lorenzo Bartolini (c. 1834)

I studied philosophy at the universities of Lausanne, Vienna and Bern, and I am currently finishing my PhD thesis on the concept of political consent (what does it mean to consent in politics?). My areas of specialization lie in early modern philosophy and contemporary political philosophy. I also have a keen interest in ethics, Ancient philosophy, and public philosophy. Thomas Hobbes would be my favourite philosopher, not because I agree with all of his conclusions, but because I love the clarity, precision and comprehensiveness of his writings.