Thank you Mr Wynn P Wheldon for such a significant question!

Michel Foucault wrote extensively on this subject. My answer will be based on some of his insights.

First let us understand what is meant by the word “humane”. We usually mean “merciful”, which implies that somehow incarceration is a “softer” kind of punishment than direct physical harm. Corporal punishment used to be very common, but we seem to have grown sensitive towards bodily autonomy and physical violence. Perhaps we have become more merciful and have transcended our old “barbaric” ways.

However, Foucault argued that what we are witnessing is not a change for the better or humane, but rather a more sinister and subtle shift in the strategies of power employed by governments and scientific institutions, especially in the last two centuries. Corporal punishment was immediate, specific and visible, and its aim was the perpetrator’s body.

Incarceration, on the other hand, has a mediated, systematic, and multi-layered effect. Foucault’s idea was that incarceration is designed to produce an experience of subjectivity that is suited to the needs of capitalism. In the first instance, those who can not participate in the market (criminals, the mentally-ill, the sick) are closed off from society and kept in institutions where they are either converted to well-adapted individuals or incarcerated indefinitely. This incarceration is justified by scientific jargon, especially certain terms of psychiatry.

The story does not end there, however, as people are pushed towards expressing themselves and acting in ways that will keep them safe from incarceration. So that very same jargon also shapes our understanding of our mentality. This means that the idea of incarceration directly influences our ways of being in the world, and we try to discipline ourselves to avoid such an eventuality. In other words, incarceration is not only concerned with the incarcerated, but it is also a tool that can influence the so-called “free” persons.

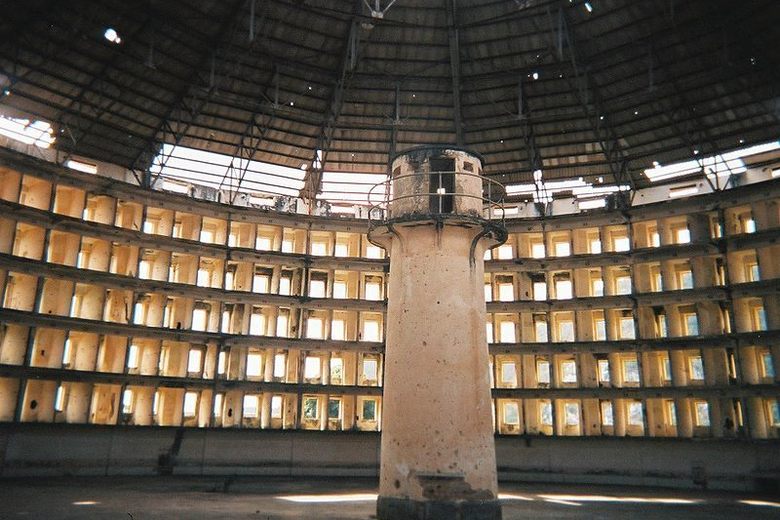

The panopticon is Foucault’s analogy for this structure of power; there is an invisible gaze that may or may not be watching you at any point in time. You cannot risk getting caught, so you have to adapt to the ways in which this gaze wants you to act and think. This is something that corporal punishment cannot accomplish. The government could harm you physically, but this may not result in a change of your personality or your understanding of yourself. Foucault’s argument is that incarceration functions in precisely this way: it aims at the very core of your personality and forces you into a kind of self-censorship. We may still call incarceration “more humane”, but that might not necessarily mean “less harmful”.

What do you think? Is incarceration worse than corporeal punishment? Let us know in the comments.

And, as always, if you have a question for the Armchair Philosophers, don’t hesitate to get in touch. You could send us a message or fill in this form.

Be sure to check out our podcast!

If you like what we do, you can support us by buying us a coffee!

Image: Inside one of the buildings of the Presidio Modelo

I completed my MA and PhD at the Philosophy Department of Boğaziçi University. My main areas of research are history of philosophy, social and political philosophy, and moral philosophy. My dissertation was on Kant's account of conscience, so I had to work through most of Kant's texts. He is my favorite philosopher because he revolutionized the philosophical scene in Europe and still continues to be influential to this day. He was one of the first philosophers to work out a comprehensive system which integrates several areas of philosophy, and he has given me a remarkable sense of what philosophy can be.

Of course Foucault liked a bit of physical punishment himself, didn’t he? In fact I think he thought it COULD change one’s personality in some way…