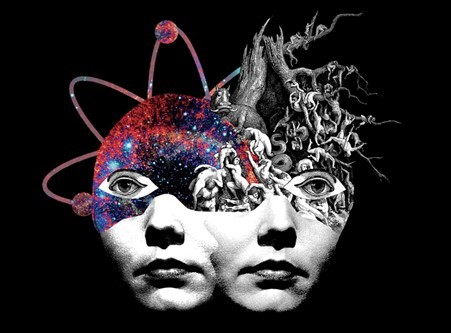

The premise here being that emotional people are not mentally able to concentrate deeply on complex problems after a point of time when faced with personal or social turmoil. Maybe that’s why most scientists remain disconnected with the world.

Thank you Bipul Verma for an intriguing question.

The point is that some people have a character trait, which we may call ‘emotional insensitivity’, that has disposed them to be disconnected and concentrate on complex problems, and therefore become scientists. This suggests that such a character trait is a necessary virtue; that is, failing to have the virtue amounts to failing become a scientist. But is this true?

The first person who comes to my mind is the great philosopher and mathematician Bertrand Russell, whose political and social activism cost him a prison sentence – yet his achievements stand.

Notwithstanding people like Russell, there is a class of emotions that are necessary for scientific enquiry. Think of emotions like interest, curiosity, intellectual courage (to question and correct your beliefs). These emotions are called ‘epistemic’ because they direct our minds towards ‘episteme’, which in Greek means ‘knowledge’, the Latin equivalent being ‘science’. Back when natural science was in the cradle, Aristotle contended that it was another epistemic emotion that made men to philosophize, namely, ‘wonder’.

Wonder and the emotions I have listed above are all positive, but there are some ugly emotions that also seem to play a role. Think of ambition and vanity. All too often academics are swept over by them. And, indeed, they do often contribute to successful enquiry. Take their influence in the politics of Royal Society, for instance, in the rivalry of Newton and Hooke, who helped lay the foundations of modern science.

However, although there are people like Tesla (a prominent recluse), there are also scientists who work together in mutual trust – another emotion that contributes to scientific enquiry at various stages.

To return to the truth of the claim, it is of practical importance to remain detached; that is, the less one participates in the world, the more time one has to pursue lines of enquiry, with less chance of distraction. But this is not to say that the less emotional, the better the scientist or mathematician one is or will be.

What do you think? Is emotion good for science? Let us know in the comments.

And, as always, if you have a question for the Armchair Philosophers, don’t hesitate to get in touch. You could send us a message or fill in this form.

Be sure to check out our podcast!

If you like what we do, you can support us by buying us a coffee!

Image: (credit)

I did an MEng in Civil Engineering at Cardiff University and an MA in Philosophy at the University of Warwick. I spent some time studying Nietzsche and the history of philosophy, but since then I have focused mostly on the philosophy of mind and philosophy of emotions. One of the most recent ideas I have found interesting (and crazy for our standards) is the revision of panpsychism (coming in varieties like protopanpsychism). This is the view that mental properties may ultimately be fundamental like physical properties. If this is right, then it may be that in the future, psychophysical laws are going to explain the conscious experiences associated with the physical processes explained by physical laws.