Excellent question, Huka Dabaso!

This is actually something I have thought about quite a bit. Like many people, before I studied philosophy in a formal sense, I was pondering the same big questions that philosophy has been dealing with since… well, since we started wondering. In his Metaphysics, Aristotle says that philosophy began when man first looked up at the stars in wonder. It was in that moment when we were finally free (enough) from the pains of mere survival and began searching for answers that humans became philosophical beings. Fast forward to the Middle Ages and philosophy begins to shrink into specializations, retreating from its position as a way of life and into stuffy rooms where jargon-armored intellectuals argue over nuances in ancient texts.

Okay, it’s not quite that bad, but it can definitely seem like it from the outside. Medieval universities in Europe kept philosophical education away from the public sphere, and the art of philosophy came to be seen as abstract and reserved for the privileged – and that’s a view people still have to this day. However, to be educated in philosophy still had some social currency. Nowadays a philosophy major is often seen as impractical, juvenile, and generally a waste of time; while philosophy outside of universities is shelved with New Age metaphysics or poorly written Stoic self-help manuals.

Institutionalized philosophy is highly specialized, and this can create an intimidating environment. The squabbling makes it hard to see the forest for the trees, and philosophy forgets how to see itself in the context of the greater human experience. By limiting itself in this way, it loses the wonder to which Aristotle referred. However, the level of proficiency expected within institutional philosophy leads to tight thinking and clear exposition of that thinking. Your arguments need to be solid and your sources carefully reported. This is where public philosophy gets into trouble.

Public philosophy, in its eagerness to explore those corners left dark by the academy, often finds itself stuck in the darkness. Logic, epistemology, and philosophy of language are hardly touched in favor of romantic metaphysics and a disregard for true investigation. This lack of academic rigor is partly why public philosophy is swept into the bin by institutional philosophy. A good example of this is philosophically-minded MMA coach Firas Zahabi. He is held in high esteem by sports fans, but if his jiu-jitsu was as loose as his philosophy he’d be tapping out constantly. His quotes are often misattributed and his use of terminology exposes his lack of understanding. That being said, what he expounds is creative and wise. He might attribute a concept to the wrong author or use the wrong jargon, but his concepts are solid and his use of them coherent. He’s got the technique down; he just needs the academic rigor to make it world class.

The reconciliation between institutionalized and public philosophy must happen with the individual. We must each honor our philosophical nature by being open to wonder, while carrying that disciplined, rigorous approach developed in the institution – do that, and philosophy will be stronger than ever.

What do you think? Can public and institutional philosophy work together? Let us know in the comments.

And, as always, if you have a question for the Armchair Philosophers, don’t hesitate to get in touch. You could send us a message or fill in this form.

Be sure to check out our podcast!

If you like what we do, you can support us by buying us a coffee!

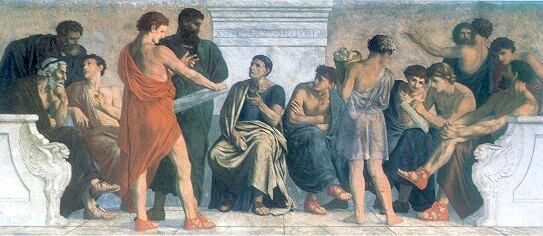

Image: Aristotle’s School, by Gustav Adolph Spangenberg (1800s)

I received a BA in philosophy from the University of Texas at El Paso in 2008. After that, I spent roughly a decade traveling Europe and North America as a touring musician. Now I am working on a master’s in philosophy and philology at the University of Gothenburg in Sweden with the goal of teaching at the university level. Some specific areas of interest include medieval grammar and free will. Michel Foucault’s approach to the history of philosophy has been a huge influence on me, and his work on notions of the self and power structures bring history to the present.