It seems we mostly create the systems afterwards to justify whatever outcomes we want.

Thank you, Ben Horspool, for a significant question.

It is certainly true that we do our utmost to justify our choices and aims. A lot of time and effort is spent trying to fit our choices and actions to a moral standard that is considered “acceptable” by our society. Furthermore, we tend to come up with explanations for these actions that represent our character in the most righteous manner. Why do we go to all this trouble if all we are truly interested in are “results”?

I think we need to consider how we come to understand ourselves and others as moral agents. Moral facts are different from physical facts in that one cannot immediately grasp a moral event without the proper moral upbringing. Barbara Herman calls this “moral literacy”: it takes a certain literacy to be able to recognize choices and actions as morally significant.

The reason for this is that moral systems are not just principles that are “out there” to make it easier for us to choose a specific course of action; they are the standards by which we attempt to measure the conduct of others as well as ourselves. It may be argued that we are seldom truthful in our self-assessment, but it would almost be impossible to have a concept of self without recourse to some standard for conduct.

Now, what might our attitudes towards moral systems be? We might know the associated norms of a system and choose to transgress them; we might know the norms and follow them while thinking they are wrong; we might act in a way that conforms to the norms for other reasons; or we might sincerely adopt them in our actions.

What we cannot do is have no relation whatsoever to a moral system, as we cannot understand ourselves without any recourse to any moral system. We need to convince ourselves that we follow at least some standard, in at least some situations. Even sheer survival or pure egoism is a moral code of some kind, by which we can make sense of morally significant actions. It would be very difficult to have any sort of self-understanding without any appeal to moral standards for conduct. Even people who commit horrendous crimes might see themselves as followers of a higher moral standard.

Also, there are cases where we can understand an action only with reference to a specific moral system. Think of Buddhist monks setting themselves on fire as a way of protesting injustice. This is a case in which a moral standard can overrule even the instinct for survival. Certain acts of self-sacrifice become impossible to explain if all we are doing is retrospectively justifying the outcomes that we wanted. There must be instances where our moral standards determine our actions. Again, self-knowledge is a very difficult task, so is self-criticism, but moral systems have always been integral both in our conduct and in our self-understanding.

What do you think? Are moral systems important? Let us know in the comments.

And, as always, if you have a question for the Armchair Philosophers, don’t hesitate to get in touch. You could send us a message or fill in this form.

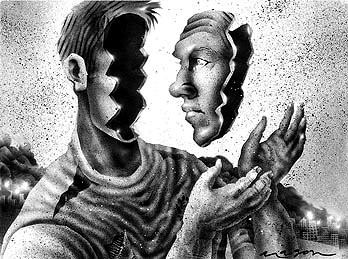

Image: (credit)

I completed my MA and PhD at the Philosophy Department of Boğaziçi University. My main areas of research are history of philosophy, social and political philosophy, and moral philosophy. My dissertation was on Kant's account of conscience, so I had to work through most of Kant's texts. He is my favorite philosopher because he revolutionized the philosophical scene in Europe and still continues to be influential to this day. He was one of the first philosophers to work out a comprehensive system which integrates several areas of philosophy, and he has given me a remarkable sense of what philosophy can be.