Thank you, Ramón Mansilla, for a great question! Let’s hope ignorance isn’t bliss, because here comes some knowledge…

If someone were to call you ‘ignorant’, then you would usually take it as an insult – that is, if we regard ourselves rational agents who are epistemically responsible and see ignorance as a bad thing. By ‘rational agents’ I mean persons who are able to freely adjudicate arguments and evidence and form their own conclusions about the world. As rational agents, we have an epistemic responsibility to try to discover the truth about the world. We also have a duty to others to pass on accurate information. This is even more pressing in a world of fake news, deep fakes and misinformation. In the current milieu, for example, lives can be lost to coronavirus through lack of knowledge concerning social distancing. The question raises several others: What is it to be ignorant? Is ignorance bliss? Is this always a bad thing?

Ignorance is usually taken to mean a lack of knowledge or information. In this sense, ignorance can be ‘passive’ – perhaps a person simply lacks the motivation to apprise themselves of the facts, or is simply apathetic. It could be that a person wilfully chooses not to apprise themselves of the facts – maybe it is through fear of the unknown, to protect themselves or others, or an unwillingness to learn. However, we can note that ignorance, in a very loose sense, is indeed bliss. For example, it is not necessary that everyone know everything. Consider knowledge of the means to launch nuclear weapons. Society is in a relative state of bliss since not everyone (in fact, very few people) have knowledge of the means to launch nuclear weapons. In this sense, lack of such knowledge leads to societal bliss. However, what I take to mean blissful here is simply the absence of pain. If we take bliss to mean subjective states of pleasure, then certain thought experiments could illuminate our initial question. Enter the Experience Machine chamber (a thought experiment first suggested by Robert Nozick).

This thought experiment invites us to imagine a chamber in which a person has their brain hooked up to a simulation which would result in perfect happiness for them. Perhaps within the chamber they have the perfect life – a high flying career, a trophy husband or wife, adorable kids and a well-liked and virtuous character. Perhaps, more mundanely, the person simply receives jolts of electrical simulation resulting in states of pleasure without any life narrative. Either way, the person in the happiness chamber would be totally ignorant of the outside world. In this sense, ignorance would appear to be bliss. But perhaps the person lacks authenticity, a true life narrative and real relationships which are constitutive of a good life. In this sense, the happiness chamber perhaps shows that whereas ignorance is bliss, it is not constitutive of a good life.

I now want to think of ignorance as simply a lack of knowing something. In this sense, it is perhaps more neutral. For example, I may lack knowledge of something simply because I have reached the limits of my cognitive capacities or range of my senses. Lack of knowing in this sense is more an appreciation of what we know about ourselves and the way we are designed. There is also a sense in which the more we know, the more we realise we don’t know. This is because new data, arguments and theories have implications which throw up other data, arguments and theories. There is certainly a sense of mystery about human nature. Perhaps, then, we have found a way in which ignorance arising from a sense of mystery about the universe leads to ‘bliss’. And if not bliss, then acceptance of what we cannot know.

What do you think? Is ignorance bliss? Let us know in the comments.

And, as always, if you have a question for the Armchair Philosophers, don’t hesitate to get in touch. You could send us a message or fill in this form.

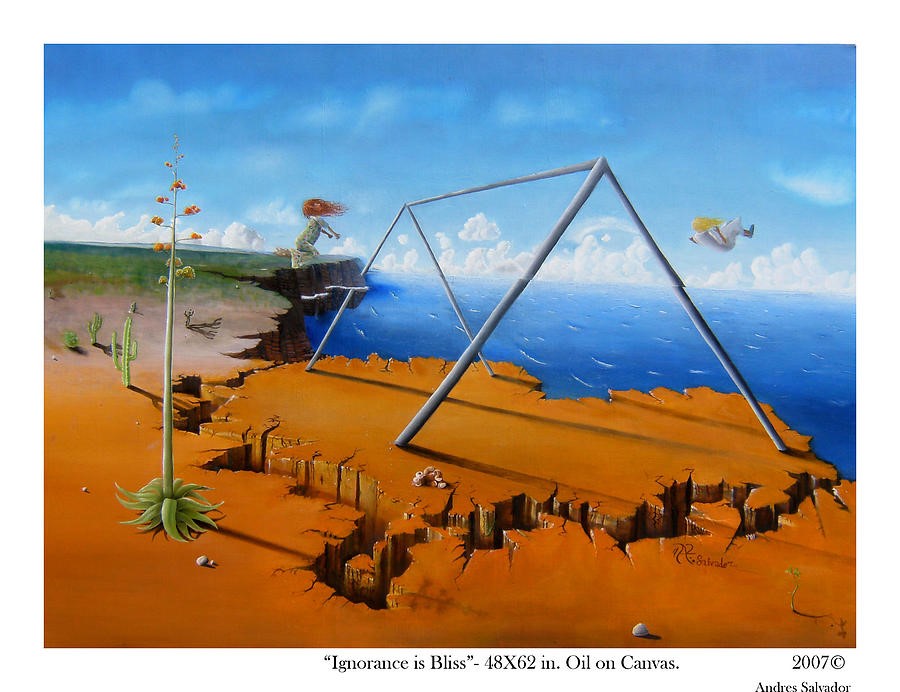

Image: (credit)

I completed a BA Philosophy (Lancaster) and MA Philosophy (Birmingham). I am due to speak on Plantinga and extended mind cognition, at the Tyndale Conference 2021. I have accepted a place on a Ph.D course starting in 2021, in the philosophy of science. My favourite philosophical idea is necessity de re(the necessity ‘about the thing’), which looks at whether things have essences (essentialism). It is surprising that in the 20th century, modal logic, which is the logic of necessity/possibility, has intellectually motivated two areas: God’s existence (with new modal ontological arguments) and human nature. Perhaps the two are connected!